KRISTEN PEYTON: THE FUNCTION OF LIGHT OCTOBER 13- NOVEMBER 26, 2018

POISED SPACE

It is one of those lovely balmy late summer days, not too hot, the sun gently wraps itself around you as you sit quietly on a porch with a dear friend, all feels just right with the world. Such is the invitation to enter the space of Kristen Peyton’s paintings. They invite us to lope in, sit down and spend some time. We know these spaces, this atmosphere. There is an air of nostalgia. The places are familiar. We are at ease.

There is a grace and serenity to Peyton’s paintings. They bid us to linger, to stay a while. We feel the warmth of the light and the air. Though for all of the nostalgia and familiar- ity the paintings elicit, ultimately, they are not spaces we have the privilege of strolling about. They are taut. The act of painting, of applying the paint to the support—what one might collectively call the concerns of painting—is always present. Swaths of paint perform a dual purpose framing the space of the paintings and obstructing our en- trance. As we descend into the space we are pushed back, held at bay by the conventions of painting. This is, I believe the brilliance of Peyton’s work, the moment between the beckoning to enter and the tension produced as we are reminded, nudged if you will, back into acknowledging this is after all a painting we are looking at. The reminder that it is mere paint on a support that we are looking at frees the light and the color to take center stage. But only for a moment until the space itself calls you once again to come close. And so it repeats again the dance between the space we fall into and the one constructed by paint.

Peyton is attracted to spaces. An interesting space is what often initiates a painting and usually it is tied to the way light is responding to and defining that space. In the painting Row House, a sequence of window frames, one set of muntins overlapping another, sending our gaze further into the space of the painting and through an arch- way followed by yet another window, relies heavily on the language of painting. A series of frames within the frame. There is a sense of the space between windows, yet the muntins perform as reflexive references to conventions and thereby keep us out. As if police tape has been strung across. One is both inside and outside the space of Peyton’s paintings. This concomitant act of framing is exactly what invites us to enter the space of the painting while also holding us just outside of the world of the painting. In Row House the muntins hold each individual pane of glass, offering a separate parsing of the space, while the overall frame contain- ing the smaller individual frames is layered over yet another frame with similar panes finishing still further beyond with an archway. The framing device asserts a passageway for us to enter. It creates a threshold to cross over. Yet the very same framing tropes synchronously assert a barrier stopping us from entering the space. It is as though Peyton is gently resting her hand on our shoulder keeping us at one arm’s length.

Orienting oneself to the façade in Quadrant Panes appears initially straight- forward enough. Our gaze is directed upward as though viewing an equestrian sculpture on a pedestal so high we must tilt our head back and tip our chin up to take it all in. In the next instant our eye is drawn to the yellow bar of paint in the top center of the painting where we are grounded for a moment only to then slide immediately down and to the right where the building appears on the lower half to come forward to form an inter or corner and at the top along the roof’s gutter to recede turning back to form a corner traveling in the opposite direction. The window acts as a framing device, further emphasized by the panes of the muntin. The window acts as a framing device, further emphasized by the panes of the muntin. In fact, the architectural structure as a whole is composed of a series of rectilinear shapes and forms with the occasional mark noting a branch asserting it as the plane of the painting nearest to us. Peyton uses the conventions of painting to create a tension between the psychology of the space, something we are invited to enter into, or so it seems, and the application of the paint serving as a wall that keeps us from falling into the space of the painting. The pink and lilac-colored wall along the bottom of the façade sits tight to

the surface of the painting while the windows above point to an interior space. The reflections on the glass, in turn, push back out at us. The window to the right of the corner further confounds the interior space as we gaze through the window to see what appears to be a swimming pool in what would be the inside of the house. It is not certain whether we are looking through the window or if the win- dow is reflecting back at us. In this sense we are both inside and outside of the painting.

In his discussion of Claude-Joseph Vernet’s Landscape with Waterfall and Figures the art his- torian Michael Fried notes “...the fracturing of perspectival unity... makes it virtually impossible for the beholder to grasp the scene as a single instantaneously apprehensible whole and by so doing tends further to call into question—to dissolve as it were beneath his feet—the imaginary fixity of his position in front of the canvas.” Peyton’s invitations to enter and the gentle touch of her hand at our arms-length shoulder force us to vacillate between the imagined world of her painting and the literal space we are standing in front of just outside of her painting.

In her book On Longing Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Susan Stewart notes “...the major function of the enclosed space is always to create a tension or dialectic between inside and outside, between private and public property, between the space of the subject and space of the social.” In the paintings selected for this exhibition, which is titled The Function of Light, Peyton plays on the tension between public and private space inviting us in only to leave us standing outside. While this may sound like a criticism, it is not. In fact, it is a rather necessary dichotomy. The paintings play on the sense of the familiar, an air of nostalgia to put us at ease. She draws us in, offering places we feel we know, places we have spent time. Nostalgia acknowledges the passing of time as light reminds us of the passing hours in a day. There is a dual sense of time, one reflective of private moments the other more literally grounded in a concrete passing of time as the sun makes its way across the sky. This allows Peyton to unite two worlds: the world that she creates for us to fall into and the one of the artist married to the language of painting. In both instances she offers us a contemplative, meditative space to be absorbed into where time stands still if only for a fleeting moment.

Elizabeth Mead Williamsburg, Virginia 2018

KRISTEN PEYTON’S STATEMENT FOR FUNCTION OF LIGHT

Color in essence is a function of light. Where light exist, color follows—illuminating space and form.

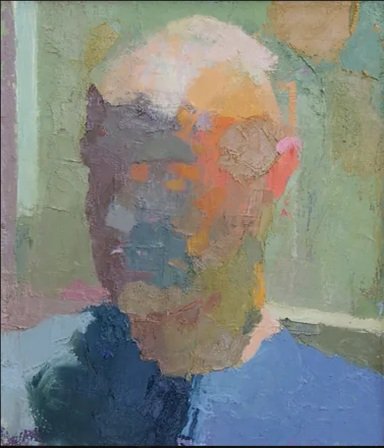

What holds the work together as a body in The Function of Light is not so much a common subject matter, but an exploration of color and color’s shape. Much of my work lacks figure or set-up, as I find myself more inclined to search for painting possibilities in the visual experiences of my everyday surroundings. My work, rather, is an active response to moments of visual surprise encountered naturally in daily living. I respond to a surprising interaction of color or an intriguing interplay of geometric shapes by which I can foresee a painting. Most often I am interested in small, unassuming scenes that present instances of visual tension and release.

My work aims to express my first impression and reveal my search for the aesthetic essentials of a chosen moment. I invite my perception of light and color to guide my image-making process and let intuition lead the way. I invent, omit, and simplify whenever necessary to arrive at a pleasing balance between observation and memory. My aim is to bring my viewer to profound presence by making known the poetics of color.

SPONSORED BY CHRIS HARRIS OF REFUSEORDINARY

AND BRIAN FREER OF HEALTH JOURNAL

Kristen Peyton

Kristen Peyton is a painter and printmaker working from observation and invention. She earned a Masters of Fine Art in Painting from the University of New Hampshire in May of 2017 and a Bachelor of Arts from the College of William and Mary in 2012. Kristen is a native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and a resident of Richmond, Virginia. She is the Director and Curator of the Flippo Gallery at Randolph-Macon College and an adjunct professor of studio art at Randolph-Macon and William and Mary.

She has exhibited works in curated shows across the East Coast and in New York City, including Blue Mountain Gallery’s 2018 winter and summer Juried Exhibitions, juried by Betty Cuningham and John Yau respectively, as well as Linda Matney Gallery’s Celebration of Female Artists, Manifest Gallery’s MASTER PIECES, First Street Gallery’s MFA National Competition, juried by Lance Esplund, and the Oxford Art Alliance’s Juried Show 2017, juried by Tom Pardon, in which she received the First-Place Juror’s Prize.

To see Kristen’s work and CV, visit KristenPeyton.com.