Jayson Lowery: Material Thought, Measured Form

Jayson Lowery’s sculpture operates at the intersection of material intelligence and conceptual reflection. Working with stone, iron, and bronze, Lowery treats materials not as neutral carriers but as active agents—each with its own history, gravity, and resistance. His forms evolve slowly, shaped by lived experience, urban observation, and a sustained inquiry into how ideas accumulate, fracture, and endure over time. Across works such as Cissoid and Locus, Lowery explores containment and release as parallel states rather than opposites. Dense internal cores, pod-like chambers, and partially divided forms become metaphors for belief systems, emotional pressure, and generative rupture—structures that hold, strain, and sometimes open.

Rooted in processes that honor material histories—hand-built iron furnaces, reclaimed architectural stone, bronze cast for longevity—Lowery’s practice reflects a deep attention to entropy, transformation, and the persistence of memory embedded in matter.

In the conversation that follows, Lowery reflects on how these materials and metaphors emerged through lived experience, studio practice, and sustained attention.

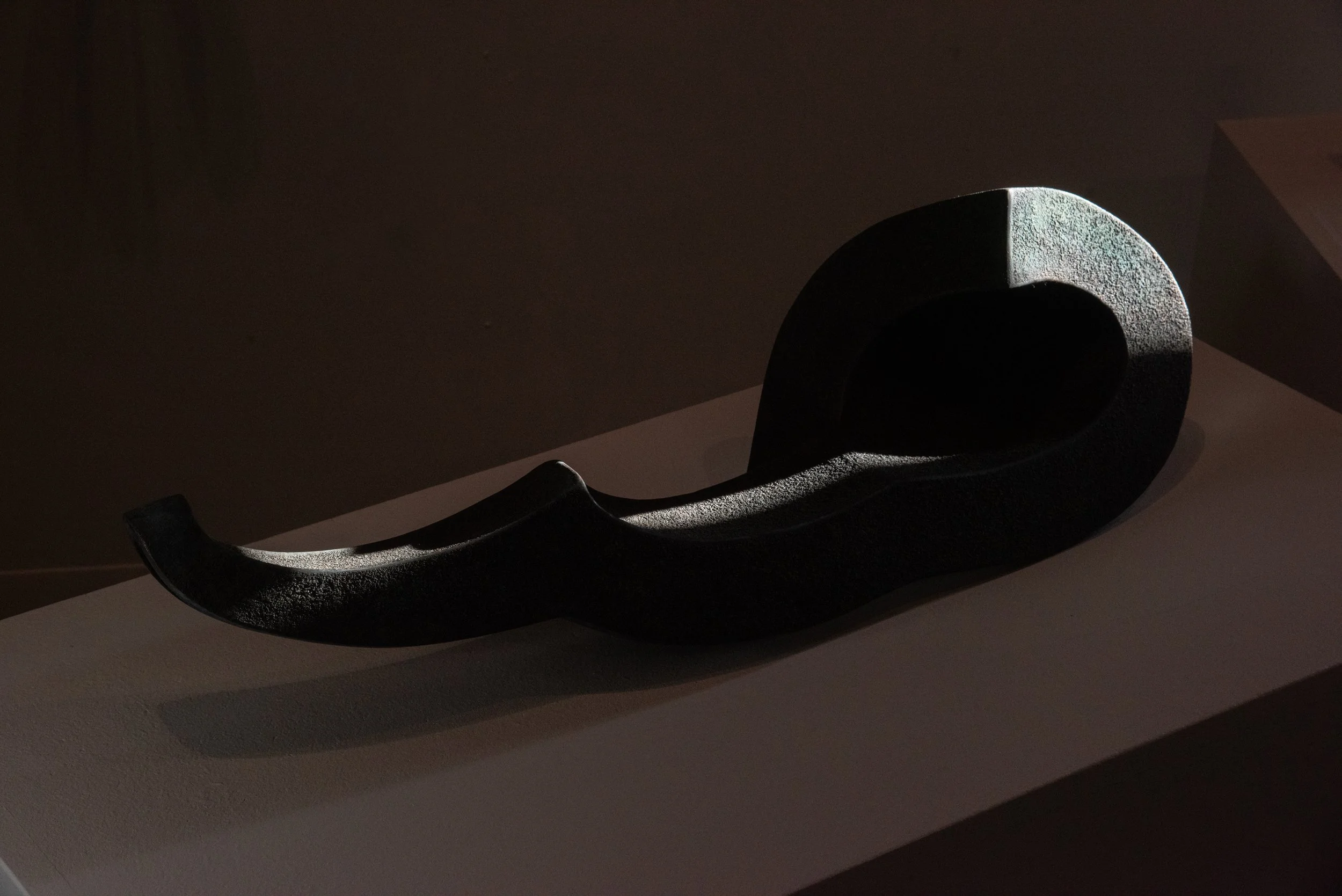

Locus, 2006

8.5”x 8”x 30”

Bronze

Locus, 2006 (detail)

Lee Matney:

I’m here with Jayson Lowery, who has brought two sculptures to the gallery. Can you tell me about the works, Cissoid and Locus and what’s behind them, both conceptually and in terms of process?

Jayson Lowery:

Cissoid was the first piece. It grew out of an experiment I did in graduate school. I used a hot-stamped steel ball, about the size of a shot put, that was originally manufactured as a cap for wrought-iron fencing. Welding fence was a job I had for a summer before moving to Detroit, so that material stayed with me.

I forged copper into a bowl-like form with flanges that fit around the ball, riveted it together, and made something that, for me, became a physical metaphor. The iron ball at the center has the potential to crumple and destroy the copper around it. At the time, I was thinking about how ideas can be destructive, how an idea can take over and really disrupt or damage a life.

A year or two later, I continued working with that idea but wanted to shift it. Instead of the core being the hard, destructive element, I began thinking about what happens if the core is made of stone. I started carving rounded stone forms, sanding them down, and using them as the basis for waxes in a foundry process. That shift was about flipping the metaphor. Ideas are not always destructive. Sometimes they are generative.

I also wanted to explore that with a more positive mindset. I made several pieces during that period. Lee sold one of them maybe ten years ago now. With these two works, I also became interested in having more than one chamber in the form. I was thinking about something between a bubble and a spirit level, the idea of a form that might split, but not completely. That partial division suggested something generative, something pod-like.

I started wondering what it would look like to have multiple versions of that form, and what it might be without the stone core. That is how the second piece, Locust, came about, the one cast entirely in bronze.

Cissoid, 2006

9”x 11.5”x 12.5”

Marble and cast iron.

Lee Matney:

So Cissoid is the one with cast iron and stone, and Locus is bronze?

Jayson Lowery:

Yes. Cissoid continues a process I had been working with in earlier sculptures, which I called Afterthoughts. Instead of naming them Afterthoughts with numbers, I decided to name this one Cissoid . The title came from a mathematics book I found in a used bookstore in Detroit. I was flipping through diagrams and charts and did not really understand what they were describing, but one of the terms was “cissoid,” which refers to the way curves meet. That outline felt similar to the form I had been working with, so the name stayed with the piece.

Lee Matney:

That sounds like a kind of serendipity. Does that happen often in your work?

Jayson Lowery:

Yes. In a lot of ways the work is meditative. I am mulling over whatever is happening in my life and noticing what keeps sticking in my mental filter. If something keeps resurfacing, an image, a thought, a feeling, that is usually a sign it is going to work its way into the sculpture. Those forms become metaphors for me. I do not really expect other people to extract the same meanings, and I am comfortable with that. The work holds those ideas for me more than it is meant to communicate something specific or literal.

Lee Matney:

You mentioned ideas being destructive. What was happening at the time that you were thinking about that?

Jayson Lowery:

I was living in the Detroit area while attending Wayne State University. I was thinking a lot about race, class, and how groups of people choose to associate, or not associate, with one another. I was not from there, and it felt very different from how I grew up in Phoenix. I had this image of people locking themselves together while remaining very separate, which felt strange and troubling to me. That was part of what I meant by the destructiveness of ideas. At the same time, I was thinking about black holes, how they pull everything in, crush it, and how nothing can escape. Certain ideas behave like that. They trap you. You can become obsessed, depressed, unable to let go. I also started thinking about gravity, not just as a scientific concept, but as a metaphor. Ideas can have gravity. They can pull you in and hold you there. Cities function in a similar way. They pull people and resources toward them, consume those resources, grow, and sometimes burn out or go dark. That cycle, the pull, the use, the breakdown, was very interesting to me.

Locus, 2006

8.5”x 8”x 30”

Bronze

Lee Matney:

I know exactly what you mean. Sometimes ideas sound good, but they do not really address what a place actually needs.

Jayson Lowery:

Yes. A lot of things sound good in theory, but they do not help the immediate, real conditions people are living with.

Lee Matney:

I am fascinated by these pieces. Why did you choose cast iron and stone for one, and bronze for the other?

Cissoid, 2006

9”x 11.5”x 12.5”

Marble and cast iron.

Jayson Lowery:

I was working with cast iron first, and that grew out of other sculptures I was making using architectural stone, fragments from facades, steps, and window sills around the city. Those stones were cut with very regular geometry, which was different from the rough quarry stone I had worked with before.Around that time, I became interested in cast iron drainage grates throughout Detroit. Some of them would steam, which I had never seen before. There were old steam tunnels under the city from earlier industrial systems. I started carving channels and recesses into stone and using wax to form elements that referenced drainage grates or windows, ambiguous structures that could be read in different ways. I was also working with steel, and cast iron made sense alongside that. The sculpture program I was in involved iron casting, and I later worked as a technician. You build a furnace, smash up old sinks and radiators, feed them into the fire, blast air through it, and melt the iron down. It is an all-day process. The iron in Cissoid came from a furnace I built myself. Bronze, on the other hand, carries different connotations. I worked with it a lot as an undergraduate. Materials have personalities. Wood has warmth. Stainless steel feels cold and technological. Aluminum looks solid but feels deceptive when you pick it up. Iron and steel feel strong, but they are temporary. They rust and decay. Bronze has warmth and a kind of softness when you work it. It is almost buttery when you weld or grind it. As it ages, it changes color, but it does not flake away. It can last thousands of years. I was curious how that permanence would change the feeling of the form.

Lee Matney:

The forms feel pod-like. You explored seed pods later, did you not?

Jayson Lowery:

I did, a few years later. After getting married and becoming a father, that experience was hugely disruptive and incredible. It made me think more about generative forms and transitions between phases of life.

I tried working with doorways and other ideas, but they did not feel right. Pod forms, growth, containment, dispersal, made more sense. I focused on that for several years.

Lee Matney:

What are you thinking about now?

Jayson Lowery:

More recently, I have been thinking about the breakup of my marriage. Again, about things breaking apart. I came across an idea from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the weighing of the heart against a feather. There are forty-one or forty-two moral denials that a person must make, explicitly stating what they have not done. Reading through them, I was struck by how many align with modern morality and with the Ten Commandments. That led me to think about making a series of sculptures involving stone, welded steel, and the feather, objects that feel broken or ruined. It is not literal or symbolic in a one-to-one way. It is more of a general emotional guide, a meditation on regret. I do not know how long I will stay with it, but that is where my thinking has been.

Lee Matney:

So the work functions as a meditative practice rather than something meant to be decoded.

Jayson Lowery:

Exactly. It seeps into the work. It is much looser than that.

Lee Matney:

We were just talking about decay, and earlier you mentioned an artist that brought to mind your graduate advisor at Wayne State.

Jayson Lowery:

Yes. My graduate advisor and supervisor at Wayne State, John Richardson, encouraged me to look into the concept of entropy. At the time, I was not familiar with the term or its broader meanings. Beyond things breaking down socially or in communication, entropy is also used in science, particularly physics and cosmology, to describe systems losing order over time. Ideas like heat death, where energy disperses and structures slowly collapse. That led me back to thinking about black holes and stars, things that pull everything into themselves, consume resources, burn them up, or will not let anything escape. What I find interesting is how easily that translates metaphorically. You can see parallels in cities, in institutions, and sometimes in people. Some things just draw everything inward and do not release it. That gravitational pull, whether physical or psychological, keeps coming back in my thinking.

What emerges in Lowery’s work is not a fixed narrative but a system—one that mirrors how ideas circulate through institutions, cities, and personal histories. Meaning is not imposed but accrued through material decisions, duration, and attention. This way of working invites a slower mode of looking and a deeper respect for the quiet labor—conceptual, physical, and editorial—that allows form to remain open rather than resolved.