The Task That Is the Toil – Sharing Our Dreams and Nightmares

Brian Kelley

“Easy is the descent to Avernus; But to retrace your steps and come out to the air above, that is the task that is toil.” Virgil

Gallery view, from left, works by Eliot Dudik, Art Rosenbaum, Kent Knowles, and Noah James Saunders.

Works from left by Michael K. Paxton and Miles Cleveland Goodwin

Artists Janice Hathaway and Len Jenkin in front of a sculpture by Richard Downs

It was probably destined to be a dark and stormy night. As I walked into the Linda Matney Gallery for the opening reception to “The Task that is the Toil,” a group show curated by John Lee Matney, a few cracks of thunder could already be heard in the distance. There was more to come. By the end of the night, the storm rose to flash floods, but at this point in the early evening, there were only a few sprinkles and two large crows loitering outside.

Normally, I would not want to mention all of this setup for an art exhibition, except that the nature of the show is about addressing this particular moment our world is in. We have spent the last year-plus dealing with plagues. I doubt I was alone in this regard.

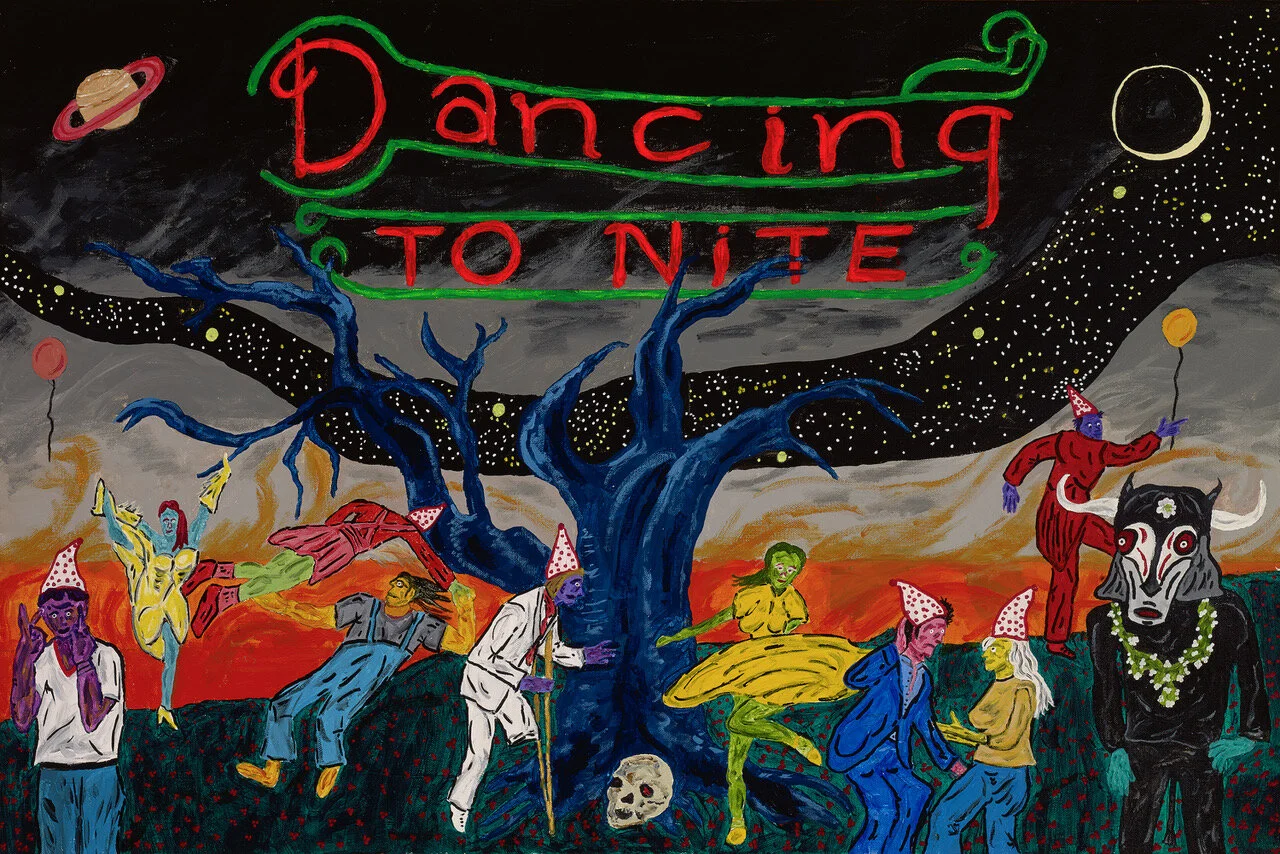

Sidney Rouse

The artist Sidney Rouse, playing the role of house DJ, had put on the ambient album of Caretaker, “An Empty Bliss Beyond This World.” The music has the quality of old swing-era jazz, if it were to be summoned out of an abandoned and haunted dancehall. It sounded like a nostalgic dream. Shortly after entering the gallery, I looked at Len Jenkin’s “Bacchanal” (2018, acrylic on canvas). The painting is a dance scene of figures, possibly human, possibly demons, around an old tree and the cosmos. Above them floats a neon sign in the style of a 1920s nightclub that states, perhaps ominously, “Dancing To Nite.” Jenkin, who was at the reception, described the figures as possibly dancing forever, creating an endless party. This party may be more something from Sartre’s “No Exit” or St. Vitus’ Dance if the figure dancing with a missing leg is any indication. At the very center of the composition is a gnarled tree with a skull vanitas at its base, a reminder of our mortality. The painting and its dancers reminded me of the reception itself. A moment later, with the rain now in downpour, a damp couple entered the gallery and everyone inside broke out in applause for their arrival.

Len Jenkin, Bacchanal, 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 24 × 36 in, 61 × 91.4 cm

This combination of the storm, Caretaker’s jazz, and Jenkin’s “Bacchanal” created my first impression of the show. That Rouse had picked this music that went so well with the Jenkin piece seemed guided by good luck, or synchronicity. Another way to think about synchronicity is to consider the Jungian idea of the collective unconscious. John Lee Matney’s original concept for this exhibit in fact came from reading works by Carl Jung in 1994. It was through Jung that Matney found the quote for “The Task that is the Toil,” a passage from Virgil’s Aeneid. The quote is literally about leaving hell or returning back to the world after a nightmare. For some, this is explicitly society emerging from Covid-19, though on the individual level there could many other personal interpretations. John Lee Matney, as he was organizing the show over the summer, would tell me that artists he was meeting with over the last few months seemed to be caught up spontaneously in some kind of zeitgeist that was beyond obvious explanation.

John Lee Matney, Jeremy Ayers, 2021-image from the 1990s, Archival pigment print, 8 × 10 87/100 in, 20.3 × 27.6 cm, Edition of 15 + 1AP

Eliot Dudik , Matthew Grason, 7th South Carolina Died, 256 Times, Archival Pigment Print, 32 x40 in

Unlike many topical exhibits currently up responding to Covid-19, January 6, BLM, climate change, or other related hot topics, the work in the show mostly avoids explicit connections. Many works predate Covid-19, often by many years. For example, Kent Knowles’ “Untitled” of the dour girl with a face mask is presciently from October, 2019. John Lee Matney includes in the show his own photography with “Jeremy Ayers” (2021 – image originally from the 1994, archival pigment print). Ayers was an important figure in the art scene of Athens, Georgia, which Matney and many of the artists in the exhibition have strong connections to. It was in Athens that Matney first encountered the Virgil quote.

Art Rosenbaum, Self Portrait with Philippine Graveyard, 2010, Oil on canvas, 56 × 33 in, 142.2 × 83.8 cm

Another major art figure from Athens is Art Rosenbaum, a figurative painter who has been a colleague and teacher to many other artists in the show. In “Self Portrait with Philippine Graveyard,” (2010, oil on canvas), we see Rosenbaum as if transported from the studio into a hellscape. Still clothed in casual studio attire, with a brush in one hand, a green glove in the other, and a compact fluorescent spot lamp to the side, he stands in front of a pile of skulls and another gnarled tree. This time, unlike in the Jenkin painting, the tree is on fire. Rosenbaum appears as a witness to the tragedies of history, and a reminder that such tragedy is not new.

Brian Freer, Lincoln, 2021, Acrylic on canvas, 48 × 30 in, 121.9 × 76.2 cm

Looking further to the past, two Williamsburg-based artists have work about the American Civil War. Brian Freer’s “Lincoln,” (2021, acrylic on canvas) portrays the Civil War president, with a face that seems both noble and weary. Freer took the concept of “The Task that is the Toil” to Lincoln’s struggle to save the country from falling apart and the tragedy that he never lived long enough to see the later peace and progress. Eliot Dudik’s “Matthew Grason, 7th South Carolina Died, 256 Times,” (2013-2015, archival pigment print) is part of the photographer’s Still Lives series, portraits of Civil War reenactors after they lay “dead” from a simulated battle. While lying on the ground, the young man in Confederate gray stares directly up at the viewer. What would it mean to “die” hundreds of times in a reenactment of a war that one’s ancestors lost? If Freer’s Lincoln dies tragically just at the exit of Avernus, perhaps Dudik’s Grason is forever stuck a bit deeper underground. Related but not quite within the scope of the Civil War is Miles Cleveland Goodwin’s “Deposition from the Church” (2018, mixed media on canvas). The abstracted figure of the painting, initially that of an old church in the South, transforms into something more of a wandering ghost or Klansman in the night. “Deposition from the Church” hangs next to “Matthew Grason” in the show. The two works reinforce a sense that trauma and oppression in our history and society has a way of lingering, haunting and reviving.

Michael K. Paxton, Lump of Coal, 2011, Ink on Drafting Film, 24 × 36 in, 61 × 91.4 cm

Miles Cleveland Goodwin, Deposition from the Church, 2018, Mixed media on canvas, 30 × 40 in, 76.2 × 101.6 cm

During the isolation and quarantines from Covid-19, Michael K. Paxton spent his time considering the larger world of illness. He is a cancer survivor and has relatives who have had black lung, the occupational disease of coal miners. Paxton has made a large body of work in painting and drawing on the topic, in what is a highly abstract take on figuration. For example, he has made works from sonagrams of black lungs, creating strange landscapes from the parts of the body that are normally invisible. In “Lump of Coal,” (2011, ink on drafting film), the lump is drawn with an energetic hand that partly swings around the form. The coal is not an inert rock, but something alive, charged. Paxton is another artist with connections to Athens, and he was part of early talks for the concept of this show.

Vanessa Briscoe Hay, Dream of John Seawright, 2001-printed 2021, Archival pigment print, 12 × 16 in, 30.5 × 40.6 cm, Editions 1-10 of 10 + 1AP

Tonight

Tonight sleep would be punishment – name your crime:

The moon high at the end of every street,

A map turned inside out around our feet.

The language where your name and my name rhyme

Translates these streets as streams;

The green light, spotted silver light

Calls the streets up like moths; tonight

You’ll waste all that you spent on dreams.

John Ryan Seawright

Karen Allison, The Virus Hunter, 2021, Archival pigment print, 14 × 11 in, 35.6 × 27.9 cm, Editions 1-20 of 20 + 2AP

Vanessa Briscoe Hay, of the Athens band Pylon, has a painting in the exhibit, “John Seawright,” inspired by a dream she once had. After Seawright, her friend and poet, had died, Hay had a vivid dream of seeing him at a cocktail party deep in a forest. Seawright tells Hay to stop worrying about him and then read her a poem. Accompanying the painting is Seawright’s, “Tonight,” a poem about nocturnal reverie. Looking at the painting, its greatest surprise is that cast shadows and light which come out from the radiant yellow house of the party. While the form of the house follows the rules of linear perspective, the shadows do not. They seem governed by a dream logic. Karen Allison, the manager of the Athens band Love Tractor, follows not a dead poet, but an art historian into the great unknown. In “The Virus Hunter,” (2021, archival pigment print), Allison follows Mike Richmond, the art historian, as he walks down train tracks. Wearing a cowboy hat and wizard robes, he is a distinctly Americana version of the shaman archetype.

Sidney Rouse, Forbidden Needs I, 2017, Gelatin Silver Print, 16 7/10 × 11 in, 42.4 × 27.9 cm, Edition of 30

Sidney Rouse, Forbidden Needs II, 2017, Gelatin Silver Print, 16 7/10 × 11 in, 42.4 × 27.9 cm, Edition of 30

The working method for many of the artists, if not all of them, is to work intuitively without a preplanned concept or idea of what the final work will be. This point came up repeatedly as I talked with artists at the reception about their work. Sidney Rouse, also from Athens, is possibly the clearest example of this intuitive approach. His photographs inherently have a surreal quality. Portions of different human figures are grafted together in “Forbidden Needs I” and “Forbidden Needs II” (2017, gelatin silver print), but the technique seems more magical than technological. Rouse explained that he works with couples in the studio, photographing one in the reflection of a mirror, and the other through scratched holes in the mirror. This creates a double image within a single exposure, and elegantly avoids any photoshopping. Between these two portraits is Rouse’s “White Pigeon with Hand,” (2018, gelatin silver print), a still life assemblage that includes a severe gauntlet placed atop a dead bird. As to what the image symbolizes, Rouse described the scene as a story of how humanity can dominate a part of nature or the world, build monuments to its greatness, and then promptly move on. The little dots in the image serve as a kind of breadcrumb for human movement and progress, as well as an ellipsis between the “Forbidden Needs” pieces. While these three works are separate pieces, Matney proposed hanging them as a triptych in the exhibition, which makes them both compositionally and conceptually much more interesting.

Sidney Rouse, White Pigeon with Hand, 2018, Gelatin Silver Print, 16 7/10 × 23 in, 42.4 × 58.4 cm, Editions 1-20 of 20 + 2AP

Looking at that hand, a strange monument promptly abandoned, my mind wandered. Somewhere under the sound of rain, the flashes of cameras and lightning, I could hear someone talking about the fall of Afghanistan. I looked again at the dead eye of the pigeon.

Ryan Lytle, In the Shadows, Installation

The largest work in the show is Ryan Lytle’s “In The Shadows” (2021, faux fur, wool, PLA plastic, rugs, paint). It is an installation in a separate room. Inside is a fox from Japanese folklore turning into a human. The figure is nearly human in scale and made largely out of wool felt in vivid dyes, making it feel partly taxidermy and partly stuffed animal from a carnival. The floor in the installation room is shag carpet, connecting back to the felt, making one feel as if they are about to touch the fox even as they enter the room. As you get closer to the fox, the 3D printed teeth begin to contrast from the rest of the felt, making the fox menacing rather than playful. Then, look to the right and you will see that the fox has a cast shadow on the wall transforming into the man.

Noah James Saunders, Sun Warrior, 2017, Galvanized steel wire, motor, 37 × 27 × 10 in, 94 × 68.6 × 25.4 cm

Another sculptor, one who works extensively with the concept of cast shadows for the figure, is Noah James Saunders. His “Sun Warrior” (2017, galvanized steel wire motor) is a wire sculpture of a man, depicted from the chest up. Using various gauges and types of wire, Saunders achieves a lightness of contour that would be most natural in a pen and ink drawing. Saunders considers his sculptures to work as “prisms” in that light passing through the form is what activates them. The viewer can illuminate the sculpture with a light from their phone, creating a wall projection that moves, rotates, and distorts under their control.

Jennifer Nagle Myers, The Spine Tree Who Cried for a Whole Year, 2020-2021, Wood, mixed media, 168 × 10 × 10 in, 426.7 × 25.4 × 25.4 cm

If there is a sense of hope for the future in the exhibit, it would be in works that attempt to find a communion with nature and the world. Jennifer Nagle Myer’s “The Spine Tree That Cried for a Whole Year” (2020-2021, wood mixed media) is another tree motif for the show. This tall and slender tree is partly anthropomorphized with feet and an empathy for human sadness. Teddy Johnson’s “Forest Edge I,” (2020, oil on canvas) shows the arms of two different people with hands delicately placed near the base of a fern. Rather than dominating nature, the hands feel tender towards the plants. One more couple, likely Adam and Eve, appear in Scott Belville’s “Reunited,” (2019, oil on panel). There are layers of reality in Belville paintings. He uses trompe l’oeil and includes views of the space around the easel in the margins of the composition. Each collaged pictorial element invites the viewer to create relationships to the whole. Adam, here with his head covered by sky, holds a candle burning at both ends. Eve, with a little bird over her shoulder, pours water on the ground. Wearing loincloths, Adam and Eve are no longer in paradise. Thorns and vines have grown around them. Theirs is the ur story for toil, and the sobering act of surfacing from a dream.

Teddy Johnson, Forest Edge II, 2020, Oil on canvas, 36 × 36 in, 91.4 × 91.4 cm

Teddy Johnson, Forest Edge I, 2020, Oil on canvas, 36 × 36 in, 91.4 × 91.4 cm

Scott Belville, Reunited, 2019, Oil on panel, 27 × 24 in, 68.6 × 61 cm

“The Task that Is the Toil” is not a show that has easy answers or messages for where our world has been or where it is going. However, the work is a means of considering these questions for ourselves. Myths, folklore, and dreams are represented in the exhibition. In so many ways, we still are in Avernus, still a bit lost, but hopeful that we are not far from the exit. Our dreams of the past and visions of the future become one in this limbo.

VIEW THE EXHIBIT ON ARTSY

Other Artists in the Task That is the Toil

Iris Wu, William Ruller , Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, Linda Mitchell, Megan Marlatt, Njambi Mwaura, Michael Suter