Glenn Shepard, Taking aim. Manu National Park, Peru, 1992, 2020

Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, Libba Cotten, Iowa City, 1976-printed 2021, Archival pigment print, 8 × 11 1/2 in, 20.3 × 29.2 cm, 20.3 × 29.2 cm

MARGARET RICHARDSON ON PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE MATNEY GALLERY

The Linda Matney Gallery represents an impressive range of contemporary photographers who use photography to explore the self and focus our attention on the world in which we live. While they each display their own distinct perspectives and themes, they share some formal and thematic similarities. Predominantly black and white, scenes are variously dramatically lit, cropped, angled, and zoomed in for effect. Many works focus on the figure and include penetrating portraits, allusive nudes, and other psychologically revealing figure studies. The natural environment provides an illuminating setting or is a primary subject. Unexpected juxtaposition and fragmentation give some works a surreal quality. Beyond documentation, these portraits, landscapes, and figure studies reveal individuals becoming aware of themselves and their surroundings.

John Lee Matney, Honeysuckle Road, 2006, Archival pigment print, 12 x16 in, 30.5 x 40.6, Editions 1-15 of 15 + 2AP

John Lee Matney, Container and the Contained I, 2002

John Lee Matney, Jeremy Ayers, 2020/ Image from the 1990s, 14 x 11 in, 35.6 x 27.9 cm, Editions 1-15 of 15 + 2AP

Owner and curator, John Lee Matney, is also a photographer and multi-media artist whose artistic knowledge and personal connections have helped to build an innovative contemporary art gallery in colonial Williamsburg. A Virginia native, Matney attended the University of Georgia in the 1980s where he connected with Athens’ vibrant artistic and musical community. These connections are reflected in his work and his impressive selection of artists from the South. With a background in street and studio photography, Matney has produced fashion and editorial photography while experimenting with video clips and stills.

John Lee Matney, Rachael 2004

His subjects include Mapplethorpe-esque nudes and figure studies, quirky costume parties reflecting Athens’ cultural scene and probing portraits, of himself and his friends, as seen in soulful photographs of Jeremy Ayers.

His use of unexpected perspectives and cropping, high contrasts, and dramatic angles connect his work to other photographers in his gallery and capture distinct personalities and moods that range from sensuous and confident to pensive and searching. Matney has personal connections to many of the artists he exhibits, and his intimate knowledge of their work is reflected in solo and thematic group exhibitions in which he showcases their unique strengths and situates them among other examples to provide new insights.

John Lee Matney, Zelma, 2008

John Lee Matney, Robert and Shani, 2007, Archival pigment print

Glenn Shepard. Quispe Forest, 1992-printed 2021

Glenn Shepard, who was raised in the Tidewater region, is a childhood friend. An accomplished and acclaimed ethnobotanist, medical anthropologist, and film maker, Shepard uses photography to both document the subjects and cultures he studies and “express aspects of [his] experiences in different cultures.” His field work has focused on medicinal plant therapy, indigenous knowledge of the environment, and the cultural and ecological impacts of modernization. These themes are reflected in photographs that go beyond scientific documentation. Quispe Forest (1992, printed 2021) depicts a figure reaching for the leaf of a plant in the forest. The figure’s head is in shadows and appears as a flat silhouette while his scarf and the veins in his outstretched arm catch the light. The plant into which his hand disappears is lit up in the center of the composition; its silvery ribbed leaves are echoed in the folds of the figure’s drapery, emphasizing their symbiotic relationship

Glenn Shepard, Crystals Manu Park 2007, 2020

Glenn Shepard, Doll, Manu Park 2007, 2020

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled (peeing in the snow), 2020, Archival pigment print, 20 × 24 in, 50.8 × 61 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

Other subjects aim arrows, survey the landscape, and hold plant specimens suggesting the complementary connection between indigenous people and their surroundings. These works are complemented by close up views of children with treasured possessions, like a pet bird or doll, which convey intimate moments and a shared humanity between subject and photographer.

Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, Cortona, Italy, 1989-Printed 2021, Archival pigment print, 8 × 10 3/10 in, 20.3 × 26.2 cm, Editions 1-20 of 20 +2AP

Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, Dilmus Hall

The storytelling element in Shepard’s work connects with the portraits and travel scenes of Margo Rosenbaum. Throughout her career, Margo Rosenbaum has collaborated with her husband, artist and musician, Art Rosenbaum. Together, they have created aural and visual records of well-known and obscure folk musicians across the country. Margo’s photographs capture the energy of performances, on stage and impromptu, while documenting the personalities behind the art, as seen in portraits of painter Elaine de Kooning, writer James Baldwin, visionary artist and reverend Howard Finster, and blues and folk musician, Elizabeth “Libba” Cotton.

Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, Howard Finster, Man of Visions, ca. 1980-Printed 2021, Archival pigment print, 8 × 12 in, 20.3 × 30.5 cm, Editions 1-20 of 20 + 2AP

Margo Newmark Rosenbaum, John Hartford, Iowa City, 1973-printed 2021, Archival pigment print, 8 x12, Editions 1-20 of 20 + 2AP

The placement and lighting of Rosenbaum’s subjects, whether centered, asymmetrical, or in shadow, along with distinguishing objects or artworks for context, convey the momentary mood and environments that shape artistic creation. The act of traveling is also documented in scenes like Amtrak, Santa Fe Train (1972, printed 2021) and Cortona, Italy (1989, printed 2021), which use double exposures and multiple layers to suggest the enriching and confusing aspects of the journey.

Sidney Rouse, White Pigeon with Hand, 2018, Gelatin Silver Print, This work is part of a limited edition set.

Such visual tricks are the specialty of self-taught photographer and film maker, Sidney Rouse, who utilizes analog techniques, like mirrors and water, to create surreal illusions. As the gallery notes, his “evocative works examin[e] entropy, illusion, and personal acceptance” and are “influenced by the iconography and rituals he experienced with the Mormon temple as a child.” Odd juxtapositions suggest rituals and sacrifice like White Pigeon with Hand (2018) in which a wicker “hand,” studded with white balls and bone-like claws, sits atop a bird on its back.

Sidney Rouse, Silo #3, 2020, Silver gelatin, toned with black tea

Sidney Rouse, Practicing Heaven, 2021, Silver gelatin, toned in black tea, This work is part of a limited edition set.

Other figures are depicted in varying states of flux, suggesting both trauma and triumph. In the Silo series (2019-2020), bodies in pieces—a torso, midsections and heads—burst with flowers.

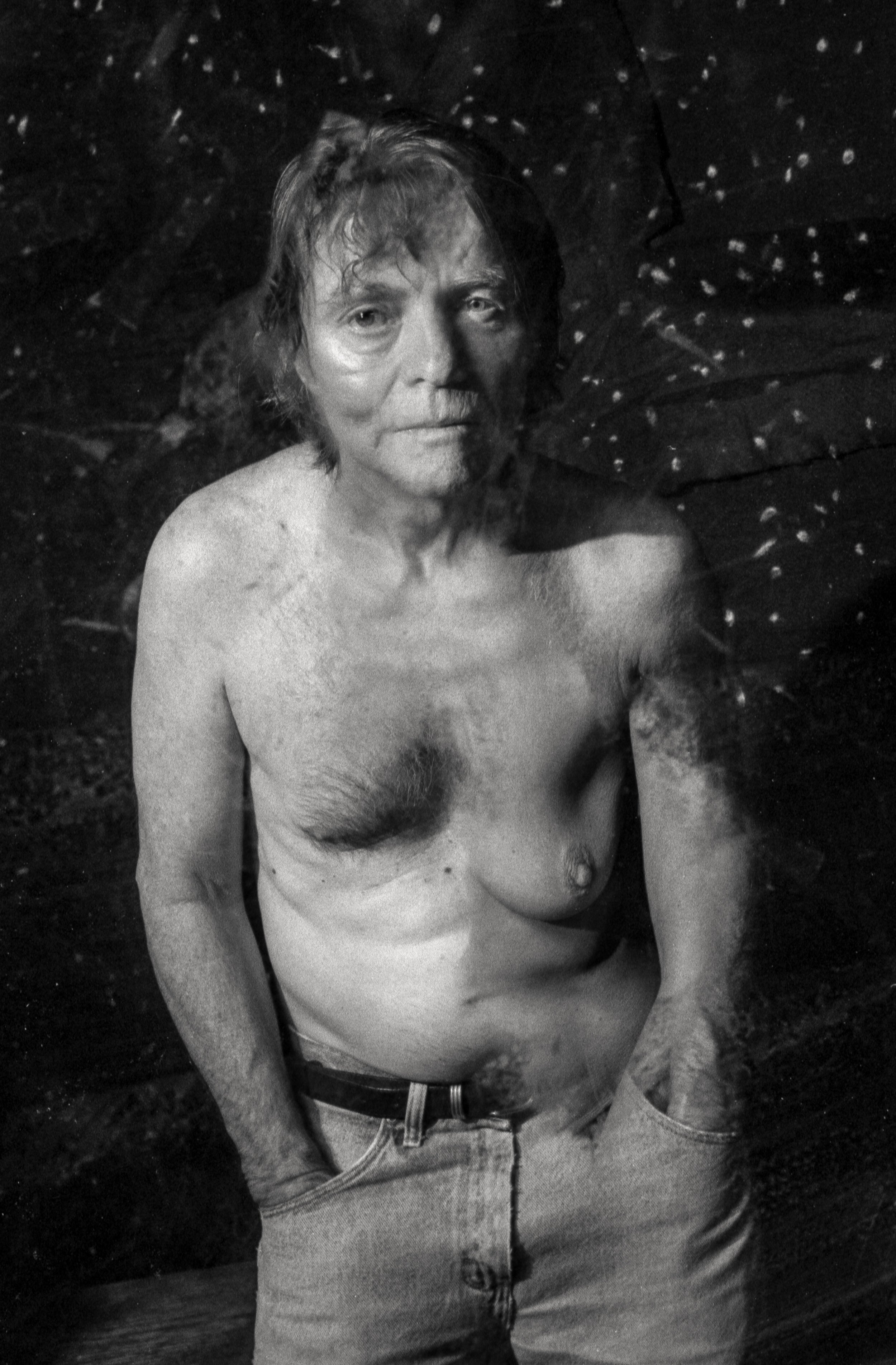

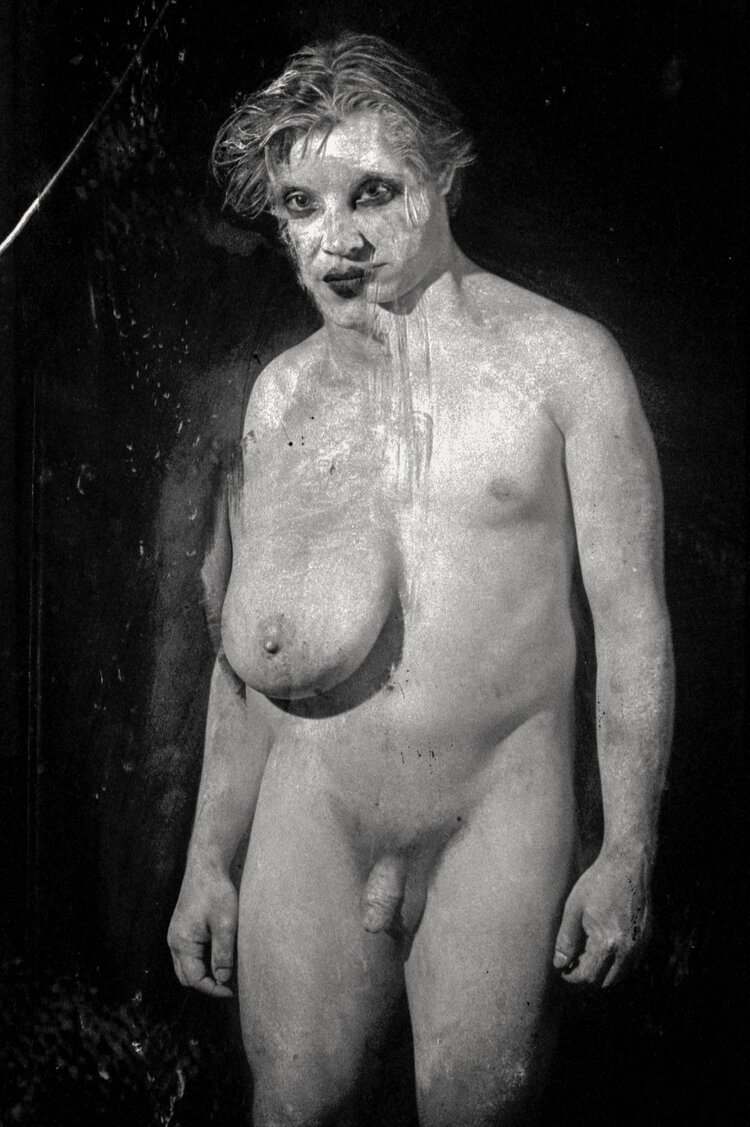

Forbidden Needs I and II (2017) depict bodies in transformation between ages and genders. The figures partially dissolve into the background and boldly stare out at viewers, confronting their gaze. Awkward and unsettling, these figures convey a sense of loss, discomfort, and new possibility that arise from self-examination and profound change.

Sidney Rouse, Forbidden Needs II, 2017, Gelatin Silver Print, 16 39/50 × 11 in, 42.6 × 27.9 cm, Editions 1-30 of 30 + 2AP

Sidney Rouse, Forbidden Needs I, 2017, Gelatin Silver Print, 16 39/50 × 11 in, 42.6 × 27.9 cm, Editions 1-30 of 30 + 2AP

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(our heads), 2021, Archival pigment print, 40 × 32 in, 101.6 × 81.3 cm, Editions 2-3 of 3 + 1AP

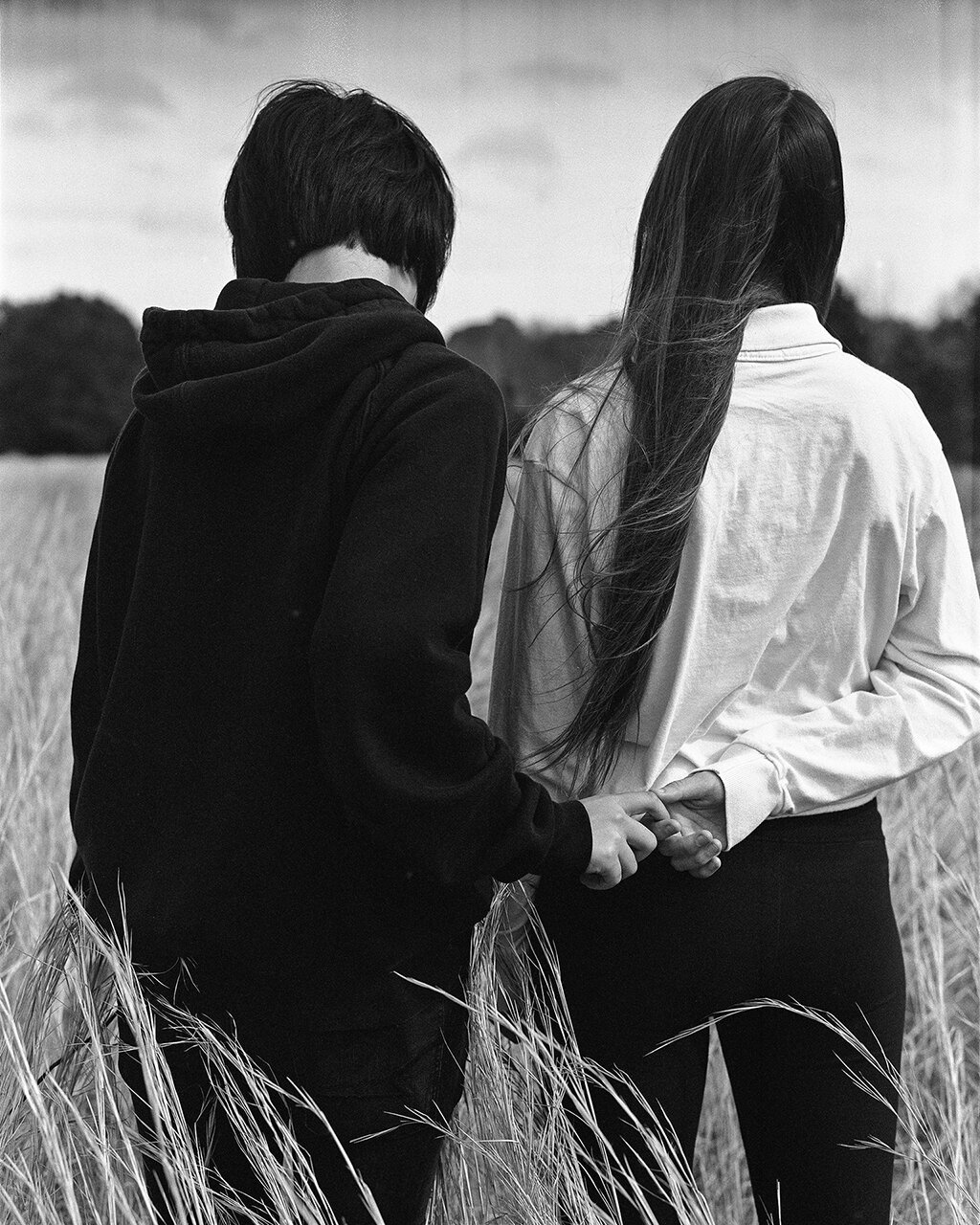

Iris Wu 吴靖昕,“Untitled (Us in the Field),” VIEW ON ARTSY

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(hug), 2019, 2019, Gelatin Silver Print, 14 × 11 in, 35.6 × 27.9 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

Living between Virginia and Guangzhou, China, Iris Wu 吴靖昕 also explores shifting and in between identities as well as memory, loss, and love. Untitled works with parenthetical notes, hug and us in the field from 2019 and our heads from 2021, capture the closeness and distance between couples. Two figures merge into one, and it is difficult to tell where one body ends and the other begins. However, contrasts of light and dark, clothed and nude, and short and long hair and blurring, cropping, and figures seen from behind suggest uncertainty and secrets.

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled (peeing in the snow), 2020, Archival pigment print, 20 × 24 in, 50.8 × 61 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(flowers), 2020, Gelatin Silver Print, 5 × 4 in, 12.7 × 10.2 cm, Editions 1-7 of 7 + 1AP

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(blanket), 2019, Gelatin Silver Print, 11 × 14 in, 27.9 × 35.6 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(self-portrait), 2020, Gelatin Silver Print, 5 × 4 in, 12.7 × 10.2 cm, Editions 1-7 of 7 +1AP

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(spilled wax), 2020, Gelatin Silver Print, 10 × 8 in, 25.4 × 20.3 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

The tenuousness of togetherness is confirmed in Untitled (self portrait 2) (2020) in which Wu appears alone and a bit lost. While Wu’s dark figure is mostly blurred against a bright background of trees, parts of the trees near her are in clear view. These images poignantly balance the fear of being found out and a need to hide with the desire to be loved and fully seen. Nature seems to offer some clarity and a little magic. In other images sans figures, lighting and an overhead perspective render ordinary subjects otherworldly as seen in the 2020 photographs of puddles embedded in a snow-covered ground and a splash of wax. While it is sometimes difficult to clearly know and show our true selves, in Wu’s images, nature provides perspective and solace.

Iris Wu 吴靖昕 , Untitled(heart bruise), 2020, Archival pigment print, 5 × 4 in, 12.7 × 10.2 cm, 12.7 × 10.2 cm

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(fruits), 2020, Archival pigment print, 8 × 10 in, 20.3 × 25.4 cm, Editions 1-7 of 7 + 1AP

Brian Freer, Japanese Scholar Tree, 2021, Archival pigment print, This work is part of a limited edition set.

These lessons of nature are evident in the photography of Brian Freer. For Freer, “photography is a meditative act.” Zooming in on nature, he forces viewers to focus on the details of the world around us. Close ups of tree bark and their textures, marks, and growths, as seen in Japanese Scholar Tree (2021), look like aerial views of larger landscapes, especially in the context of other scenes that depict trees, mountains, and waterways from a distance.

Brian Freer, Greensprings Swamp, 2020, Archival pigment, This work is part of a limited edition set.

Such a long view is seen in Greensprings Swamp (2020) which places viewers in the reflective water where the clouds in the sky look like ripples in the swamp. Creating a mirror image of sky and trees, the scene is disorienting yet pleasing in its symmetry and balance of light and shadow, earth and sky. A similarly serendipitous synergy is evident in Beech Bark with Shadows, College Woods, Williamsburg (2020) in which the tree’s mottled surface assumes the illusion of skin. While much of this work focuses on the natural world, its connection to the body and its role in locating one’s self in the world connects with other photographers in Matney’s collection.

Brian Freer, Beech Bark with Shadows, College Woods, Williamsburg, 2020, Archival pigment print,

Together, these artists reflect a quest to discover, define, and accept themselves through their connections to others and their cultural, natural, and spiritual environments. Figures are defined by their surroundings as the natural world relates to humanity. Ordinary people and objects are transformed by the photographers’ frames as they highlight quotidian details, intimate moments, natural wonders, and universal human experiences made extraordinary through their lens.

MORE PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE MATNEY GALLERY FROM REPRESENTED AND ASSOCIATED ARTISTS AND COLLECTIONS

Judith McWillie

Oleg Dou, Courtesy Deborah Colton Gallery

Eliot Dudik in Habitation 2022

Brittainy Lauback

Rob Carter

Madeleine LeTendre

Olga Tobrelut va Deborah Colton Gallery

Sandra-Lee Phipps

Kristin Skees. VIEW

Mark Edward Atkinson. VIEW

Luther Gerlach. VIEW

Diane Covert. VIEW