Brian Hitselberger Interviews Christi Harris

BH: Your Unwritten History series bears the most resemblance, in terms of genre painting, to traditional portraiture, although these are not portraits at all, but carefully rendered paintings intended to mimic aged and damaged photographs. Your statement mentions that you identify with not only the women in the images, but with the imagined damage, a quality you describe as "symbolic of life experiences changing our self-perception." That's really interesting - can you elaborate?

Christi Harris: Unwritten History Installation

CH: Women are told everyday how to look, how to act, and what is socially acceptable. I can't count how many of my friends and acquaintances who have been told they are ugly, unworthy, too fat, too skinny, too outspoken, that they should smile. On top of that, I have lost count of how many women I know who have been physically, mentally and sexually assaulted. All of these things cumulatively alter your self-perception on an individual level. You begin to believe that you deserve what has happened to you. You asked for it. You believe that you are ugly. You believe that you are fat.

On the more subtle end of the spectrum, I feel that women are not allowed to age. As I have become older, I have noticed the change in the way I am looked at and spoken to, especially by strangers. I find it really interesting that most of us hold in our mind one perfect photographic image as representative of how we look. We eternally compare our current selves to that image and are usually disappointed. We can accept the changes as part of who we are, or we can feel that they define us.

Christi Harris: "Silenced"

BH: Are mid-20th century gender roles interesting to you, or repulsive, or interesting because they are repulsive? I get the sense that your answer is complicated, because so often when explored in your work they are treated humorously.

CH: How I feel about it is complicated. I would say that in general, I find it interesting because they are repulsive. The truth of it is, very little has changed. The expression of gender roles are more subtle, yet pervasive. The women used in advertisements in the past and present show a woman who has never really existed. She is an object for consumption or a prop for sales. Historically, these ads contradict social issues, such as women in the workplace, harassment, birth control, children conceived out of wedlock, spousal abuse, incest and rape. All that considered, I prefer using imagery from the mid-20th century because it is slightly removed from my experience. It is the imagery that my mother would have grown up with. I can create continuity between her experiences and my own through a kind of magazine time-travel. (I also love the look of the color-printing process in that era.)

BH: Do you feel that your earlier work series with Cash Registers, Frosting, and Grocery Store Interiors play into a larger aesthetic project of your work as a whole? If so, what is that project?

Additional works by Christi Harris

CH: I feel that they are all intertwined as an exploration of domesticity and consumer culture.

BH:What aspect of being an artist do you find the most challenging? What aspect do you find the most pleasurable?

CH: I find the "business" aspect of being an artist the most challenging. I don't enjoy seeking venues for my work, putting together image files, forms and payment for entry into exhibits. I also find it difficult keep track of all of my expenses.

The aspect that I find the most pleasurable is the making of the work. I love watching how a group of work comes together to support an overall aesthetic and conceptual statement.

BH: What artists have inspired you and what else has influenced your practice?

CH: Like anything, the artists that inspire me change along with me. An artist I may have known about might not strike a chord with me until a particular moment in time. In my list, I have made a conscious effort to choose women. Too often, when I am asked who my favorite artists are, all I can spit out is Richard Diebenkorn and Wayne Thiebaud.

1) Julia Jacquette: I love the way her paintings mimic collages, and critique the content of the painting by incorporating text.

2) Janine Antoni: "Loving Care". It is the perfect performance piece. It incorporates traditional gender roles (mopping the floor) denial of aging (dying your hair), and the physical action and exhaustion that comes from performing these expectations.

3) Eva Hesse: Fragile, experimental, ephemeral, symbolic. She subverts minimalism and turns it into a newborn creature.

4)Toba Khedoori: Massive scale in drawing, vast expanses of paper that within its margins portrays tight, formalist drawing. The subjects of the drawings create associations and emotion in the viewer.

5) Rachel Whiteread: She makes me see the unseen.

What else has influenced your practice? Traditional "women's work" of embroidery, sewing, quilting, etc.

Christi Harris Interviews Brian Hitselberger

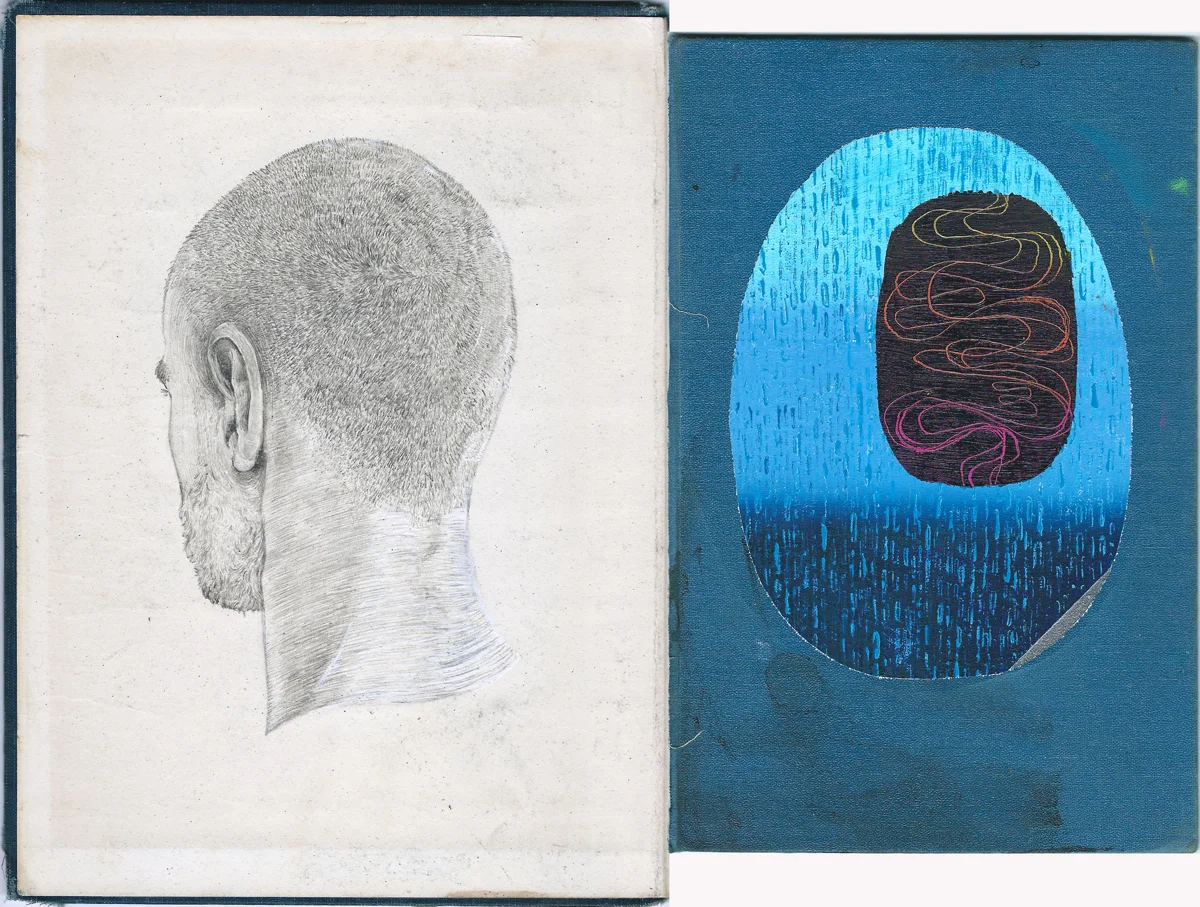

CH: You use found surfaces in your "Forgetting the Self" series, specifically hardback book covers. Can you please discuss the significance of using mismatched book covers as surfaces for your diptychs? How important is it to you where they come from (location and subject), and what kind of discolorations are present on the covers?

Brian Hitselberger: Untitled(Evan)

BH: I started using those by essentially by accident. I always have some area of my studio where I pin drawings, notes, images and postcards up on the wall - creating a space to make formal and intellectual connections between imagery, text, ways of mark-making, etc. This grouping of material generally includes everything and the kitchen sink and typically gets out-of-hand before it comes to a point where it's any use. In one of those serendipitous studio moments, I looked up and saw a quick sketch I'd made of a sleeping figure tacked on the wall next to a sky scene painted on the inside of a book cover that I'd found and worked on. I immediately noted the formal resonance of these two rectangles next to each other, each containing their own type of reality. It stuck.

"Tantra Song," -- a very important book for me -- had recently been published and I was spending quite a bit of time flipping through these images of Indian Tantra Paintings. I marveled at the sense of time contained in the painting itself, which felt so fresh, and the paper it was painted on, which read as so ancient. That visual disparity of time was really resonant with me, and I became interested in working on these distressed surfaces as a way to access that, or to put that in the work. It felt like a formal opportunity to describe the sense of time-lessness, or slowed time, that reverie and sleep (the activities the figures are engaged in) can evoke.

Brian Hitselberger: Untitled( Bill Asleep)

In terms of the sources of the covers, I have to say the original text holds little significance for me! i just head to the Habitat for Humanity and start to judge the books by their covers! I was drawn to hardcover books with fabric wrapped boards as these were, in essence, small canvases pre-stretched for my purposes. The water damage on the interior of the books was always a joy to behold, and placing and "setting" the figure inside that damage was an important formal aspect of the project for me.

CH: "Forgetting the Self" is manifested as both smaller scale multimedia framed works and as large ephemeral installations. Is one the starting point for the other, and what is the relationship between the two?

Brian Hitselberger "Night Mind" Detail -

Brian Hitselberger: "Night Mind"

Those types of relationships are very typical of the way I've begun to work within the last few years: large series of small works culminating in bigger works exploring similar formal ideas. I do tend to get to know whatever subject matter it is that I'm becoming involved with first on a smaller scale, and gather momentum until I build my way up. The ephemerality of these pieces, however, is circumstantial. Right now I'm working on a series of small works on paper that are being made alongside some larger works on canvas- so those will very much exist as discrete pieces once they are completed.

The wall drawing process and its attendant ephemerality felt really appropriate as a means to discuss the delicacy of the mental states being examined in this particular body of work. Dream states, for me, feel like really rich experiences that are fleeting - I wanted that to be reflected formally. Additionally - the wall drawing process really allows me to treat a wall of a gallery in much the same way as I would a page, placing a figure inside it in relation to its edges.

CH: You say that a sense of touch is important to you, due to your training as a pianist/musician. How do you feel about distancing the viewer from your surfaces with glass in the framed works? Am I being too literal in the sense of touch being actual rather than implied?

BH: I am thinking about touch all of the time -- it's a current that runs through everything I do, I believe. With the graphite drawing, there's definitely a concerted effort on my part to render a texture that can visually be "felt," - that's what technical skill affords us as artists, the activation of one sense through another (in this case, a sense of touch activated through the visual). But I also am concerned with how a work "touches" a viewer in an intellectual or emotional sense - this is the deeper and more longer-lasting concern for me. Piano was a wonderful way for me in my early life to begin to understand these relationships, in that the music itself, as well as the music's effects upon an audience, are literally made out of physical touch upon the instrument.

Distancing through glass - a necessary evil. I initially displayed them without the deep frames, but once I tried it out I loved how the frame and the glass finished the work. I couldn't go back! So yes, although I am an artist obsessed with touch on multiple levels, with these works it has to remain resolutely visual.

CH: In the majority of the works, the head is viewed from the back. It seems to me that I am seeing the brain in two different views, one which is figural and one which is non-objective. Is that an accurate assessment?

Brian Hitselberger: Untitled

BH: I think that's definitely fair to say, and that's certainly what I would consider the primary read of the pieces - but I try to make work that can yield multiple readings simultaneously. In placing such dramatically different modes of image next to one another, I certainly am drawing a comparison between the two - asking a viewer to consider the interrelationships between them. That's what I love about diptychs - two elements exist side by side as a means of alluding to a third.

CH: Your drawings possess an intense level of mark-making, which is delicate, descriptive, and specific to the direction of the planes. How do most people react to the pairing of a highly skilled drawing with an intuitive non-objective work?

BH: This is such a good question because it is not something I'd really thought of before! You know virtuosity and skill in art are always pleasurable to bear witness to, and I can certainly look at really skilled drawing and painting all day long. I think many viewers share this. With regards to these pieces in particular, it seems that most are drawn in by the detail, in a "oh-wow-look-at-that" kind of way, but it's my hope that the apparent disjunction between the skill and time so clearly present in the drawing and the apparent lack of this in the painting will really stay with people. Again, like I mentioned in the last question - it's all about that third unnameable thing that exists in between the two.

CH: What artists have inspired you and what else has influenced your practice?

BH: For this work body of work I was really looking a lot at Caspar David Friedrich, Anonymous Indian Tantra paintings, da Vinci's notebooks. I was also reading quite a bit about neuroscience, and the structure of the mind. But some enduring influences for me: Sol Lewitt (a fellow wall-drawer), James McNeil Whistler, Peter Doig, Ross Bleckner, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Louise Bourgeois, Paul Cadmus' drawings...... also some key writers: Annie Dillard, Italo Calvino, Gaston Bachelard, Roland Barthes and Wallace Stevens.