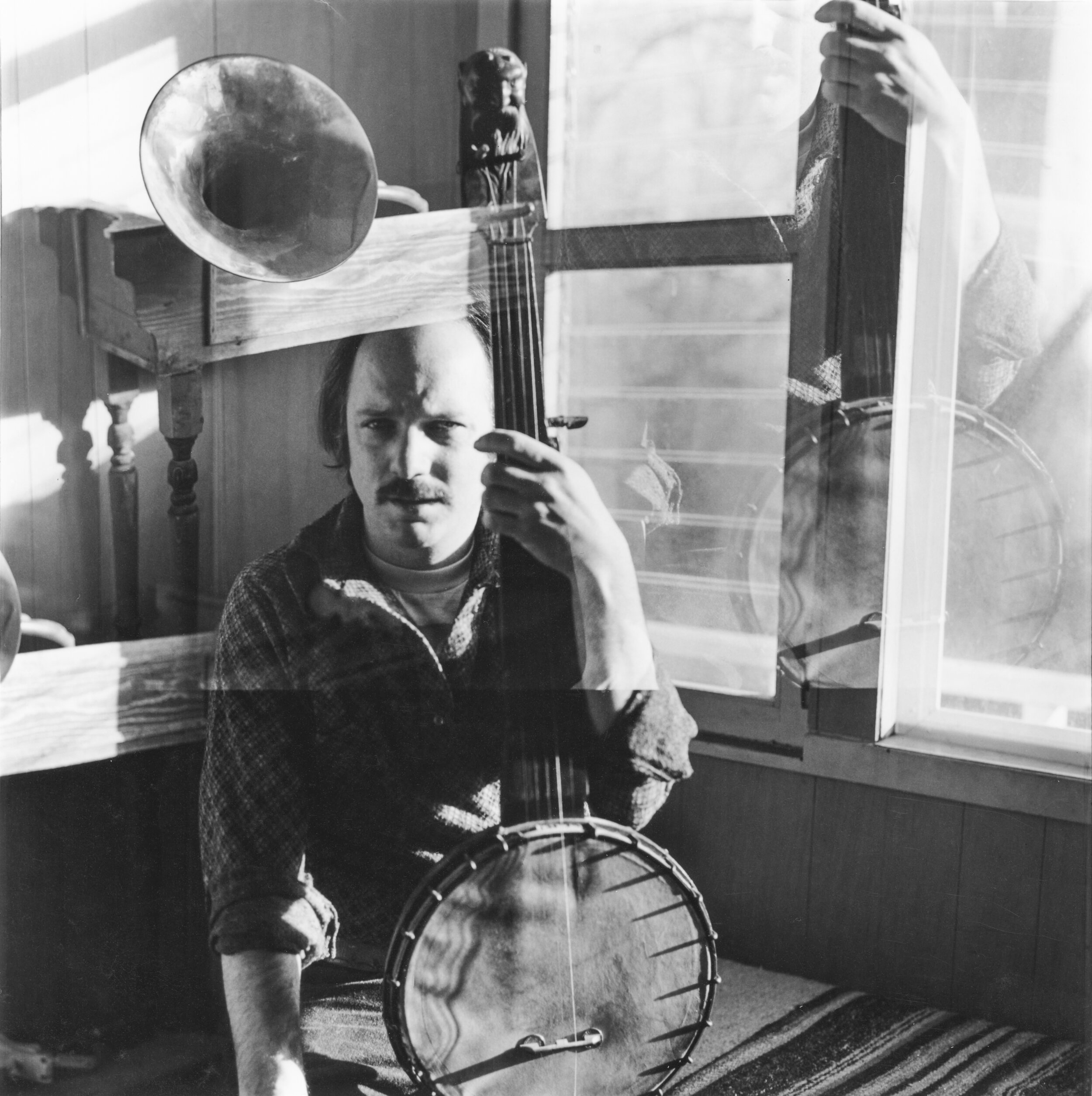

Kent Knowles in the studio

SOUTHERN GROOVE: KENT KNOWLES REFLECTS ON ART ROSENBAUM, PART 1

JLM; Cultural influencer Jeff Maisey of Veer Magazine has said: “Sometimes a painting will catch your eye from a distance and hook the viewer by the rib cage.” I understand that sentiment very well when I see the work of Kent Knowles, professor of art at Savannah College of Art and Design/ Atlanta, Kent has been represented by the Linda Matney Gallery for nearly a decade. And today, we're discussing painter art Rosenbaum and his influence on Kent's practice as an undergraduate at the University of Georgia. and today. We're also discussing Rosenbaum in a broader context of international and regional art movement movements and figurative painting.

Hi Kent, great to see you. First I'd like to ask you to talk about paintings by Rosenbaum that resonated with you as a student, and today's a mid-career artist,

Hey Lee, thanks for having me, and it's, it's great to be able to speak with everyone. I want to thank Lee for giving me this opportunity because it's kind of exciting to have studied with Rosenbaum and see his work changed over the years and of course, mine as well, but what's really fun is I knew him as my professor at a University of Georgia. I was there from 2003 to 2006. (The graduate program) is a three-year program, by the way. I didn't take my time on that. It was designed that way and one of the great things about it was that we did get a chance to teach and our studies.

Art Rosenbaum in his studio with artist Tyrus Lytton

And so, when I think about Art Rosenbaum, he was really the first person that I got to meet. I don't know if you all are familiar with the grad program at Georgia. It's pretty exclusive if I do say so myself, and they have some wonderful scholarship opportunities. So, of course, I was gunning for a scholarship, and I happened to be in the area, and Art Rosenbaum reached out to me after I'd applied and said, Hey, you want to come to check the place out? And I said, of course, and I don't know if I actually expected to get to meet with professor Rosenbaum personally. I thought I might have an administrative assistant kind of say, Hey, that's the art building over there.

But it was quite a different story. I met with Art directly, and that blew me away because I'd seen his stuff, and I'd heard about him, and I wasn't quite prepared to actually be sitting in his office. He had an awesome office, by the way. it's, it's almost like if a set designer from a film had said, Hey, we need an art professor office, you make it. , You had the skeleton there, lots of books, of course, a brilliant man. I remember there was a great Pontormo poster on the wall. Pontormo was this Italian mannerist, and he's my favorite or one of my favorites.

Art Rosenbaum in his studio, Athens, Georgia, 2017

So I remember sitting down in that dusty chair and thinking, Oh man, I'm in the right place. So Rosenbaum, of course, delivered. He took me around, and it was a fantastic experience. You get this feeling like this is where I belong. So I almost immediately had that, and it was such a pleasure. So over the years, I got to learn more about him and work with him, but that poster with the Pontormo in that mannerist style really stuck with me because I think that's something that Art does very well; he brings a lyrical quality. That's a good word for painting, especially the figures.

And the mannerist, as you all probably know, we're post-Renaissance. And so by then, they'd figured out how the body worked. they knew they knew all that stuff, and they were kind of like, eh, what are we doing now? And so, using the figure as a vehicle to extend kind of the emotive quality of the human body, I thought was right on.

Art Rosenbaum, Rakestraw's Dream, 1993, Oil on linen, 78 x 106 in. VIEW ON ARTSY

Art Rosenbaum, Howard Finster with Couple and Fire, 2006, Oil on canvas, 66 x58, VIEW ON ARTSY

I was thinking, which one should I talk about? This one, this one, does all the talking; Rakestraw’s Dream

I think this is a quintessential Rosenbaum, and what I think many people don't get right off is just how complex his compositions are. it's one thing to say, Hey, I'm going to have six figures in a painting but to be able to direct the viewer's eye from one spot to the next and to maintain a focal point and to do all of that it's not just a matter of scale or contrast. Still, you have to deal with temperature and color; You can't have everything hot at once because the viewer's not going to know where to look. And then anytime there are any symbols or text that triggers something else in the human eye that says, Oh, I need to read this first.

or I need to pay attention to this object first. I know I'm probably talking to some art people out there, so I don't mean to simplify things, but to be able to orchestrate a multi-figure, multi-surface giant canvas is no easy feat. And I think one of the best takeaways I had from working with Rosenbaum is that they would sneak up on you. The paintings would sneak up on you. So would you'd say, Oh yeah, that painting with the guy grabbing the guitar on the water. And somebody else would say, no, no, it's that painting with that shirtless guy, holding that figure., no, no, it's not. It's the one with the window, you know? There'd be such an over-saturation of information, but yet it would be so well composed that I would liken it to an excellent film. You, you don't just experience the film and then walk away; it kind of haunts you, and maybe two days later, you're still thinking about it. For me, it has always been a strength of Rosenbaum's work because it resonates with you, and I think this painting is no exception. Another thing I got from, Rosenbaum, was not just color.

But his ability to draw, because he did this equally] well, just with limited palette or limited materials. I really appreciated his work because he would oscillate between these grand paintings and these drawings. However, to maintain that type of focus still with these complex compositions, I always pulled something from that. So I really liked that he gave all of his students this green light, to be ambitious with what they do, but then to also, you know, jump around with media and see what comes out of that exploration.

Art Rosenbaum, The Studio and the Sea II, 2015, Charcoal and conte, 30 × 44 in, VIEW

KK: He was a pretty intense character. I don't know how many of you have had the chance to hang out with him, and he still has a very vigorous, studio practice just as he did 5 years ago when I knew him. But you know, he was kind of an intimidating figure in a way. He was extremely accomplished. Even before you worked with him, you were a little bit hesitant, but he was quiet about his accomplishments and didn't often meet somebody who's very humble about what they do, and he'd never kind of wore it upfront., the more you have the chance to talk with him, you started to say, Oh, Oh, you speak French., Oh, okay. And, you know, and another language,

And then what do you mean you just got a Grammy? I regret, I never had the courage to take part in the sea shanties that he would host the Gobe. I was kind of in that group. I think just overall, and it is his kind of his love for just everything that was going on while still being able to give his energy to (so many) different things: so he'll pull out,some music or he'll tell you about these great days in New York and the art collection. He sets the bar very high.

Art Rosenbaum, Untitled Diptych, 2014, Casein, 60 × 80 in. Available. VIEW ON ARTSY

Art Rosenbaum, Strainer, Oil on linen, 140″ x 84″, 2008

JLM: Comment on the legacy of figurative painting at UGA

KK: In a way, it's really a great time to be an artist right now. I think it's probably a great time to be an anything right now, but a lot of the instruction that we've had up till now and then granted we're living in a post-post-modern arts climate. Still, I think a lot of people's concepts about artists stems from Modernism, where you would have people hanging out together, writing manifestos, talking about what they wanted to accomplish as a group, making art which is splintered, in recent times, because people are globally connected now. Still, even, so you see a form of that. For example, let's take Instagram, you see a forum of either the algorithm or just your personal interests, and you start to curate what you want to be surrounded with.

And that's, that's not unlike for me finding a solid group of artists to smoke cigarettes with and drink coffee and, talk about conceptual development. So, what we have now is a version of that, but it's around the world. So I could be looking at an amazing painter from Switzerland and seeing similarities. You see this in film, and you see this in scientific discoveries and pretty much everything where there's something out there in the ether. Multiple people are addressing it and feel like it's up to the moment, but yet it's shared.

(synchronous discovery) but also you don't want to deny the potency of a kind of regional influence and whether you're going to a place specifically to study with someone or to be in a certain geographical location that, that you intend to have influenced you in some way but what I'm more interested in is the things that kind of creep out from, from under the floorboards. I can say, at least during my time at Georgia; there was a slant toward figurative work. And I don't mean it was orchestrated. I mean, it just happened. And it was fascinating because I remember we had art Rosenbaum, of course. Then we had Scott Bellville, a figurative painter, and Jim Herbert, an abstract figure painter.

And that guy was interesting too because he'd paint nude, and they'd be these 12-foot paintings he'd be hand painting.

Art Rosenbaum, Jim Herbert, 1984, Oil on linen, 50 × 42 in, 127 × 106.7 cm. VIEW ON ARTSY

( It was a) pretty amazing time, but a lot of it was all about this physicality. If you look at time in history, you can, in retrospect, start to see a correlation between how artists behaved based upon technology or just whatever's going on in the world. Things were getting kind of slick in the early two-thousands. We had smartphones and giant screen TVs. There was a real nod to acknowledging the human body for the area that I was in and the people I was around. It came in the form of figuration- synchronicity.

I'll take it.

Art Rosenbaum, Self Portrait with Camera, 2001, Oil on linen, 52 × 46 in, 132.1 × 116.8 cm, VIEW

I love the South. I love being an artist in the South because I still feel like the rest of the world doesn't quite understand what's going on here. There's that Southern mystique, which could be said of other places, but there is something very elemental about certain parts of the world, and maybe it's an oppressive heat, maybe it's a landscape, maybe it's the home of cicadas. There's something really grand about the South. I think it's probably gonna be perpetually misunderstood because, politics aside, I think there's something, there's something about the region. And when I say South, I think, you know, anything, you know, South of DC.

Kent Knowles, The Iron Triangle, Oil on linen, 66″ x 72″, 1994, private collection

JLM: Can you talk about a few of your works and how they intersect the Rosenbaum?

One of the things I took from Rosenbaum was this, this unabashed, kind of ribbon-like quality to the figure. His ability to twist them to fit within a form and have them respond to environments. it didn't hit me exactly when I was there, and I don't know how you all operate, but for me, it takes a while for things to resonate and sink in. So I was part of this experience, and it's a lot like you're discovering things about yourself. You're figuring out things with paint. So it was shortly out of graduate school, I started to see those influences pop up, and that came in primarily the way the figure was distorted intentionally and sense of pattern. Go back to that first image, what a curveball , because you have patterns on the tie, but you also have the pattern of the water, and then you have the reflections on the glass and the rocks, and the wrinkles and the fabric. So, all of those things are like a great challenge. You give a chef 15 ingredients, and you say, no, you can't just pick three. You gotta use all of them. But if you overpower us, with, with flavor, you failed. So I see Rosenbaum's paintings as like up in the ante, but there's nothing wrong with quiet or minimal work, which has its place for sure.

Kent Knowles, Alto, Oil on canvas, 48x60 in, 2013, Private Collection

KK: I always loved Rosenbaum because there was this unabashed quality. Y0u have to have a strong stomach to engage in that type of activity. So while my stuff's no nowhere near as complex as his, I always felt that his work was a visual representation of the complexity of his mind. To go from French to music to teaching, to painting, you see that you see the equivalent of that in the visuals that he created. So, of course, I'm still attempting to marry these interesting narratives that are somewhat mysterious; in his painting, there's music going on. Still, there's also something else going on, like young romance, and then there's man and nature; there's a sense of God in there.

Kent Knowles, Urchin, Oil on canvas, 72 x74 in, 2013

I remember saying, all right, I'm going to make some big surfaces, and I'm going to try to make them as complex as possible. Still, I wasn't very good at gravity, so I ended I ended up putting a lot of paintings underwater, so that, so that if the gravity wasn't quite what Rosenbaum would do, at least I had this, this kind of life preserver, pun intended, uh, to keep me, keep me composing without having to deal with gravity. But it was fun being a student too.it was a wild ride

JLM: What are some paintings that have defined the trajectory of your career?

Kent Knowles, Bloom

KK: Bloom was a pretty big one for me. I started realizing that, that I wanted these mighty girls navigating space. This was the first one, but they increasingly became in this state of danger; there was this sense of peril, and it was something that kind of surprised me. I have other images I could show you, but like there would be a painting of a girl climbing up a tree and sawing off the branches as she made her way up. I was thinking, wow, that's very self-destructive, but unlike Rosenbaum, I could only focus on one kind of protagonist, if you will an the entire narrative would anchor around that figure

Kent Knowles, Undoing

I always marveled at Rosenbaum’s paintings because he could do multiple things within a painting yet still maintain a focal point, which is not easy. In a way, his paintings remind me of a Giotto sequential fresco where one thing happens and another and another, but you're experiencing it all at once. I think it's a real testament to not only his way of designing surfaces but also to our neuro-plasticity, our ability as a human race to develop and process information, multiple bits of information all at once. So in that way, I think he's kind of ahead of his time because you have to catch up to him, not the other way around.

JLM: Urchin was in on our show Art House on City Square in downtown Williamsburg, a collaboration with the city in 2013. And this was the year after we did Substrata Tyrus Lytton. For this piece, I saw your process going on and I saw how you changed it in different ways. I really think that's exciting when you're changing something as you go, and you're using your cell phone, and you show me one version, and then another version which kind of evolved into this one. Can you discuss this piece?

KK: Sure. So you know what, so a lot of people will see a painting of mine, and again, I can't speak about Rosenbaum's work because I, I think even if he explained to us what he was doing, it'd still be a mystery., and say you decided to paint a painting of a person holding a sea urchin, surrounded by an octopus. Yet, nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the narrative always takes a back seat. It's not even acknowledged or even thought out until there's a design. This really started as it is just a series of lines that overlap and collide until a form starts to present itself. When it does, I have the wonderful privilege of figuring out how to nurture that idea and still make sure it works somewhat logically in a composition. The first underwater painting I ever did was because I had a figure that looked like they were floating, but I couldn't figure out why. I didn't want them to just be floating, although I let myself do that later.

JLM: Well I definitely see that. You are both masters of color and dynamic movement.

KK: Well, I appreciate that you know, um, and when I see his paintings, I think music, you know, as I think about, and I, I don't, I don't write music, but I know that there has to be like a crescendo. Then there has to be, you know, some rhythm that occurs over and over, and then there's some refrain, or again, I don't know music terms, but when I see his work, I think music, um, and I would love for people to, you know, have that feeling in my work too.

JLM: What are some other milestone works for your career?

KK: They're still coming along. Um, I did, there is one painting, um, and I couldn't find it regrettably, I couldn't find an image. Cause as I said, I'm a horrible, uh, documentary, but I did a painting once of, um, when I was in graduate school, that's when we had Hurricane Katrina. For whatever reason, I had a very, just a profound , emotional response to that. I remember seeing the footage and just thinking how come nothing's happening? This is America, what's going on. I remember there was a, there was a gentleman, a victim of the flood who did not know how to swim and nd so he had fastened these two giant kind of igloo coolers e to his arms, like giant floaties. I was in graduate school when that was happening, and I remember what an impact it had, and I didn't know how to handle it. So I was whacking away at these two canvases. It was a diptych or just a two-part canvas, I guess you could call it a diptych, but it was really because I couldn't make them any bigger. So I just put two big ones together, and I struggled with this thing, and it just wasn't happening. And you know, it's one of those things you hear about in, in books. , it's like one of the paintings fell over for whatever reason.

Maybe I was throwing things at it; it wasn't happening, it wasn't coming together. And so I went there to put it back up, and I said, well, what if I put it on the other side and then the painting just came together. And it was an exciting moment because before I had two figures, and one was like on a little chunk of land here andnd one was on a little chunk of land over here. And between them was this great expanse, and it was new Orleans, and houses were covered in water.

You know you could only see their rooftops. There was like an old highway that had collapsed. And anyway, what happened is when I switched them, those two little landmasses, there became an Island and suddenly all the activity was happening around this little patch of dry land and the painting just came together and it wasn't until later that I realized that Rosenbalm had a similar thing.

JLM: This is The Deluge, which is in a private collection here in Virginia.

KK: My painting was called the flood

Can you discuss Island? I love the angles of the water and this one and the reflections. Is is very difficult for you to do these reflections and hash that out?

Kent Knowles, Island, Oil on canvas, 72 x74 in, 2013

No, it's not. Because we're already dealing with non-reality, that's one thing II enjoy about my work; I'm not beholding to reality, so to speak, because I don't use references. And I think these weird kinds of lobster creatures are kind of a testament to that. I start with something.- maybe there'll be a jellyfish, and then it becomes something else, and maneuverability allows for, of course, gross human distortion, but it also allows the design to come first. What's interesting about this painting is that it's this type of view; we understand it. We can see the cross-section of, of water, like the interior/exterior. We see the surface; we see below the surface that wasn't available until film and cinematography or photography came around.

So we can say, Oh yeah, that's just a cross-section. But outside of maybe scientific illustration, people wouldn't understand why. They'd say, why is that weird triangle of foam, you know, floating above the water? We have to consider that commercials and film, and music are always conditioning us to interpret space. And when a new, new image comes along after that wears off, it just becomes part of our communal understanding of space.