Introduction by Lee Matney

Several years ago, Diana Blanchard Gross and I discussed curating a Nudes exhibition, at a time when the gallery was exploring a broad range of directions. The show brought together exceptional painters, ceramicists, glass artists, and photographers, each approaching the Nude with their own visual language and sensibility.

My interest in the figure has deep roots, beginning with early video stills made in Athens, Georgia, and continuing through photographic and studio work in Virginia from the late 1990s onward. Across time and mediums, the Nude has remained a central focus — not simply as a subject, but as a site of ongoing dialogue between tradition, personal history, and contemporary practice.

The Nude remains one of the most enduring and complex subjects in art, inviting reflection on form, identity, and the shared experience of being.

Sandra-Lee Phipps

I told him these things I’m telling you now,

from Lessons in Survival series, Jennifer

2019, Archival Pigment Print

Nudes, The Mirror, The Big Tent

Brian Kelley, 2023

The figure, the nude, is the closest thing to a mirror for ourselves in art. The scope of nude art is broad in time, going back to ancient periods. It is also diverse in approach and intention. There are ideal nudes of a kind of transcendent human form, but also imperfect, real people living in specific times and places. There is nudity that is chaste, but also nudity that is erotic, possibly even naked. In America, nudes can be inherently charged for general audiences who use terms like “family friendly” or “tastefully done.” For others, especially in contemporary art and current identity politics, there is a deep fascination with the very idea that we live corporally “in a body,” and the nude is the motif of choice for many artists to address this topic. “Nude: A Contemporary View,” the current exhibition at the Matney Gallery, curated by Diane Blanchard Gross and John Lee Matney, adeptly covers this broad subject, and exposes viewers to the state of contemporary figurative art.

There are a few wonderful contradictions for the nude and figurative art worth addressing. Here is one, as explained by David Katz in an essay for a book I highly recommend, “The Figure: Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture” (2014, Skira Rizzoli Publications):

Agnes Grochulska

Figure study with blue outline 1,

2021

Acrylic on Belgian linen

Figurative art is still one of the most controversial subjects in today’s art world. Depending on your point of view, it’s either an academic backwater or a lively contemporary dialogue.

The nude is both something old, a touchstone back to Old Masters and Classical Greek marbles, but also likely as popular as it has ever been in painting, sculpture, photography, performance art, etc. This paradox partly comes from the period of mid-20th century modernism in which Abstract Expressionists largely eschewed figurative art. Pollock and Rothko did not paint nudes. The return of figurative art, depending on whose art history you follow, does not return to center-stage until roughly the 1980s. We are now the generation after this return to the figure, forty something years on. Ideas about conceptualism, feminism, the male gaze, sexuality, gender, and critiques of standards of beauty, which were not particularly prominent during the days of the Impressionists, are now alternatively taken for granted or seen as continually revolutionary (another one of these wonderful contradictions).

You need to believe in something, from Lessons in Survival series, Vanessa, 2019

Archival pigment print

34 1/2 × 46 in | 87.6 × 116.8 cm

Frame included

Edition of 5 VIEW ON ARTSY

As you enter the Matney Gallery, one of the first artists we see is the SCAD professor Sandra-Lee Phipps, with photographs from her Lessons In Survival series. The nudes are women, referred to by their first names, reclining, floating or submerged in bodies of water. In “Vanessa,” the nude floats on her back with arms outstretched over what could be the shallows of a sea. We are looking down from above, seeing the whole figure, as the water partially submerges her and the ripples beautifully scatter light. “Isabel,” another Phipps photo, reclines in tidal shallows, her body mixing into the seaweed, staring back at the viewer in a manner not so different from Manet’s “Olympia.”

Sandra-Lee Phipps

Beauchamp

from Lessons in Survival series,

Isabel, 2019

Archival Pigment Print

Sandra-Lee Phipps

The Muddy Rushes

from Lessons in Survival series, Erica

2019, Archival Pigment Print

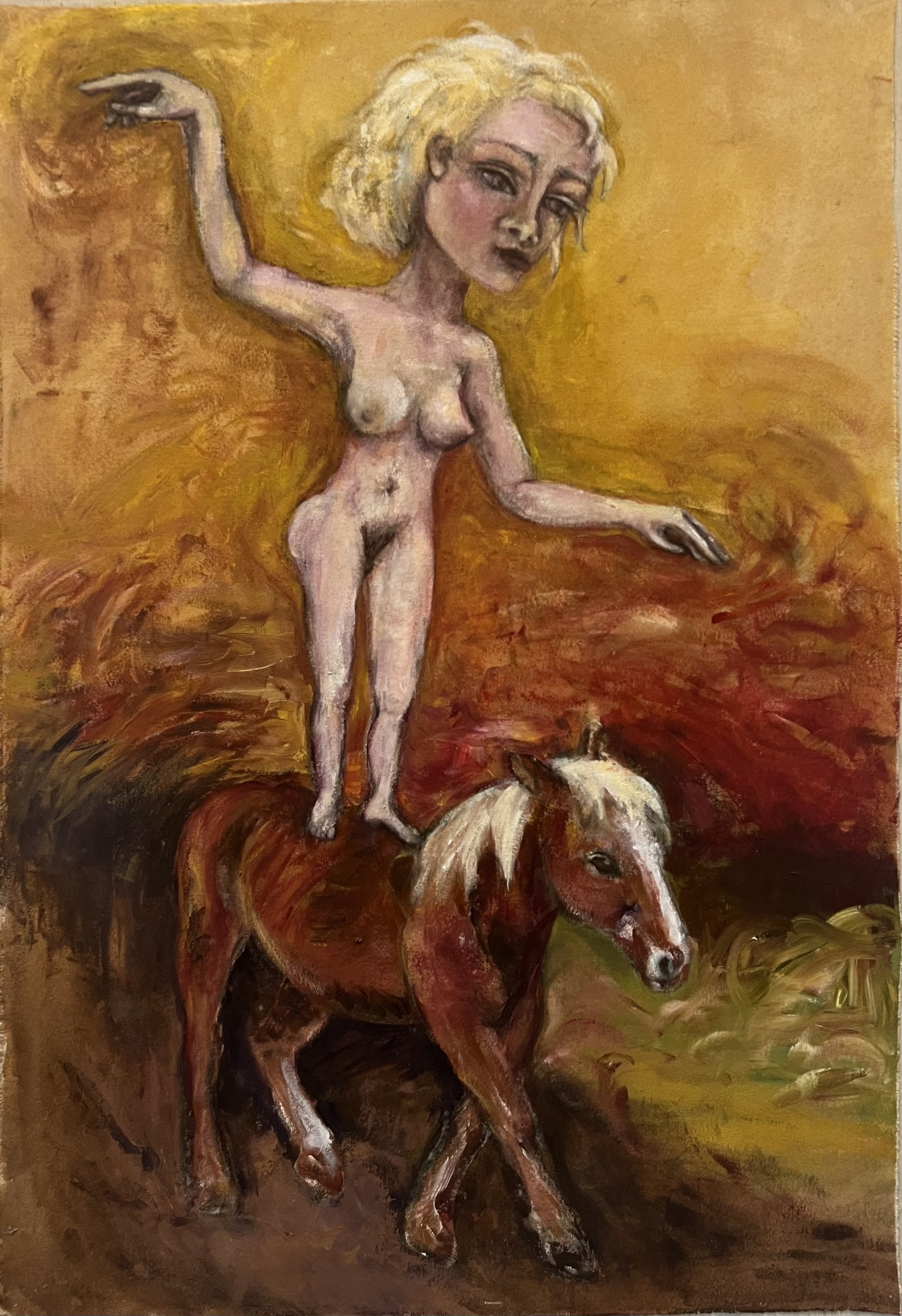

Jennifer Hartley

Bareback, 2015

Acrylic on canvas

Not all works are seascapes, however. “Jennifer,” is backgrounded by a forest, with the central figure holding a stickly trunk of a young fig tree as its leaves cover her chest. In each case, the figures exist alone in nature. There is a variety of body types and ages for these women. The nude ideal has shifted from a traditional concept of lithe youths to a more open ideal for embodying confidence and empowerment. Jennifer Hartley appears twice in this exhibition. In addition to being the model for this last Phipps photo, she has the acrylic “Bareback,” a kind of Lady Godiva mixed with the Bull-Leaping fresco of the Palace at Knossos.

Brian Kreydatus

Stephanie, 2015.

Woodcut

Brian Kreydatus

Kent, 2015.

Monotype

Another artist that wants to work with the nude partly as a form of portraiture is the William and Mary professor Brian Kreydatus. He has several prints in the show, mostly in intaglio, but also woodcut and monotype. His nudes sit on upholstered chairs and couches in what could be living rooms or other domestic spaces. That said, there are telltale signs of the professional model setup. In “Mayzie” the nude sits on a chair that has been covered with a sheet of drapery, a common method to make furniture used by nude models more hygienic. At the foot of the print is a coffee mug. The women is not actively drinking from it, but might once she breaks from the pose. If Michelangelo once said that the foot is more noble than the shoe, Kreydatus helps us to see how beautiful and strange a person’s knees can be as they bunch and bend, modeled in the light of a nearby table lamp. The possibly endless complexity of the form of the particular figure, not an ideal, is part of what makes these truly portraits and not just studies of the figure.

Sometimes the nude can be a vehicle for allegory. Mark Miltz, a local Virginia painter, clearly aims to transform his models into larger ideas. In “Dichotomy,” a nude woman stands in a dim room with strong blue and red lights with what looks like stigmata on her hands, blood pouring down like strings. The pose of the hands is also like that of Justice with her scales. Incongruously, she wears a very dressy necklace and has curled her hair. Her skin glistens as she makes direct eye contact with the viewer, looking stern.

Mark Miltz, 2020, oil

In another Miltz, “Invalid Comparisons,” (2014) a nude woman stands holding a broken Barbie doll in front of her. The doll is the same scale as the actual woman. Barbie’s head rests on the ground. We can see how the real woman’s shoulders are wider, feet bigger, waist thicker. Unlike the doll, the woman stands solidly on her own two feet. How was the doll broken? Barbie’s face is pristine, free of the stain of makeup a girl might apply to her doll, and the hair looks like it has not been lovingly overcombed. This is the kind of damage a girl’s brother might do, not the girl herself. Devon Lawrence, another local artist, has several watercolor paintings, such as “Embrace of Empathy,” that feature the same models as Miltz, as they often are at the same model sessions.

Mark Miltz

Invalid Comparison

Oil

Devon Lawrence

Embrace of Empathy

Watercolor

Chris Corson

Plinth, 2019

Pit fired clay

As in general art history, most of the show is female nudes, but there are some males. Chris Corson’s pit fired ceramic sculptures are of men, bald and middle aged. One of the most striking pieces in the show, “Plinth” is of this nude male seated cross-legged, bent forward with his forehead bowing to the ground. The pose could be one of meditation or submission. The patina of the pit firing creates imperfect mixtures of white and gray over the figure. On a vase or bowl, such a patina might have a subtle elegance. On nude flesh, it looks visceral and ashen. In an era of contemporary art that often uses the nude figure explicitly for empowerment, Corson may be using the nude for humility.

Laura Frazure

Citizen app Series: Nude Man in Lobby

2020, Modeling compound

The “Nude Man in Lobby” by Laura Frazure, who earlier this year had a solo show at the Matney Gallery, is an interesting counterpoint to the Corson sculpture. Frazure’s figure, at a foot tall, is smaller than Corson’s and is made out of a glossy, black modeling compound. The standing pose is relaxed. Frazure elongates the figure slightly in the limbs and abdomen, something she has done frequently in her sculptures.

Agnes Grochulska

Figure study with blue outline 2

2021

Acrylic on Belgian linen

If nude art reflects ourselves, it is not a literal mirror. Far from the more stereotypical and traditional concept of ideal proportions in Barbie dolls, each artist may arrive at their own personal temperament for the proportions of the figure. There are Rubenesque rotund figures, for example. Giacometti had his elongated figures; much more elongated than Frazure. Agnes Grochulska, a Richmond painter, approaches the form of the figure in a way that might be 1 part Frank Auerbach and 3 parts Egon Schiele. In “Figure study with blue outline 2,” an acrylic painting on exposed Belgian linen, the angular and gestural male nude in profile is part drawn, part painted with a mix of both naturalistic flesh tones and synthetic hot pink, lemon yellow, and cobalt blue. The raw linen serves as both the ground for flesh tones but also the negative space around the figure.

Julia Rogers

Woodland Fawn, 2022

Hot sculpted glass

Not all nudes need to be even fully human. In what feels particularly prehistoric, we have the mythical figures in glass by Julia Rogers, a glassblower at the Chrysler Museum. Her “Woodland Fawn,” is a hot sculptured glass figurine one foot tall, with the body of a woman, save for the head and forelegs of a fawn. The work is one-part the technical mastery of sculpting the figure in polychrome with glass, and one part the atavistic mystery of this human-animal hybrid. Compare this figure to the Lowenmensch figurine, a man with the head of a lion carved in ivory, dated to around 35,000 BCE. Karl Jones is another Chrysler glass artist in the show. His two works, “Green Goddess” and “Blue Beauty,” exhibited as a pair, both two-dimensional glass works in monochromatic color schemes. These works, compared to other pieces in the show, are unambiguously idealized female nudes in profile, chin up, hands covering breasts. They also have a photographic quality to them, with very strong modeling of light and shadow.

Karl Jones

Green Goddess, Fused Glass

Blue Beauty, Fused Glass

Janice Hathaway

Lady of Sensual Ecstasy, 2021

Transmorgraph

6/20 of 20

Janice Hathway also explores the nude as hybrid in works such as “Lady of Sensual Ecstasy.” Here the female nude is part plant. The head is a white and yellow blossom, and the flesh of the rest of the body has taken on the same materiality of the white and dewy petals. Hathway describes this kind of work as transmorgraphy, a kind of surrealist digital collage which obscures how the collage was made, enriching the sense of fantasy.

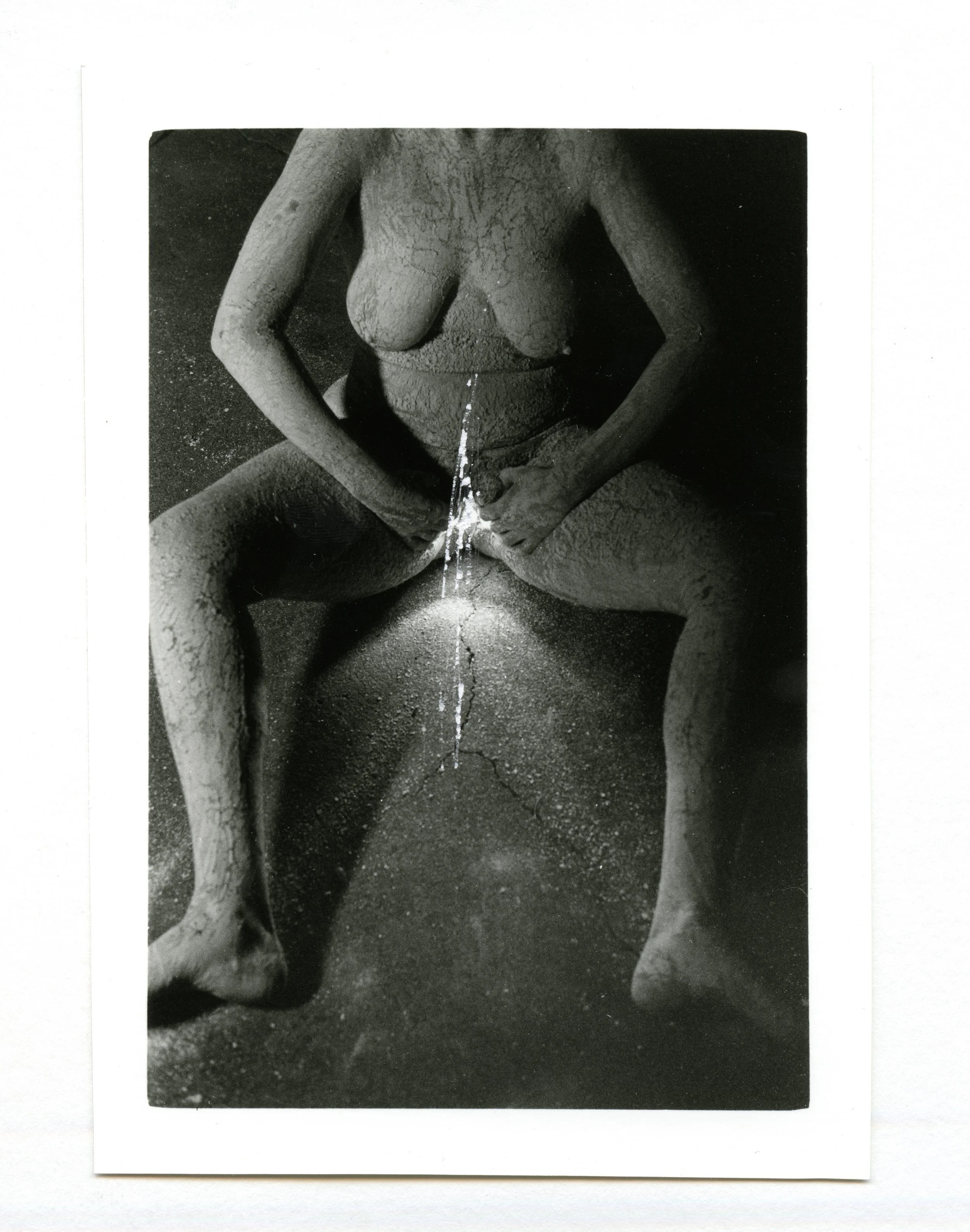

Sidney Rouse

Untitled, 2023

Photograph

A more analog kind of surrealism happens in B. Sidney Rouse’s “Inner light,” gelatin silver print, another highlight of the show. A seated female nude, whose head is cropped out of the photo, covered in dry mud spreads her legs to reveal a light inexplicably coming from her crotch. There appears to be both some kind of actual light emanating from the model, but also the print has been scratched down to the white of the paper. The effect is such that the viewer never quite knows exactly how Rouse created his photo, making this headless woman of mud feel magic.

Rebecca Shkeyrov

Born on Strange Soil, 2021

Oil on canvas

While there clearly are several fantastic and even mythic artworks in the show, the painting that seems as much about a fantastic world as well as the nude itself is Rebecca Shkeyrov’s “Born on Strange Soil.” The painting is a double nude self-portrait, first standing in the center foreground with red eyes, second sitting in the background with her back to the viewer. The place, vaguely like a landscape from the sci-fi animation “Fantastic Planet” is pink and purple with trees the green shade of lichen where they would terrestrially be chlorophyll.

With over a dozen artists in painting, photography, and sculpture, “Nudes: A Contemporary View” shows that the state of the nude is strong and highly varied. It is a big tent for art. The nude, whatever your expectations for it, is an even broader subject than any one person can initially imagine. There is no one way for the artist to work with the nude. It is a sub-genre of figurative art, like seascapes are a sub-genre of landscape art, and yet it is so large and rich that an artist could dedicate an entire career to it should they want to and never exhaust the possibilities. Also, time can warp when we look at nudes. The nudes of Phipps: are they from today or from the Garden of Eden? Are the nudes of Rogers from someone in the stone age who happened to figure out glass? A lack of clothes and a vague background means the figure might be from any place and time. It makes the nudes of art history still vital today and those of today timeless.